The Perils of Being Stranded on a Mountain

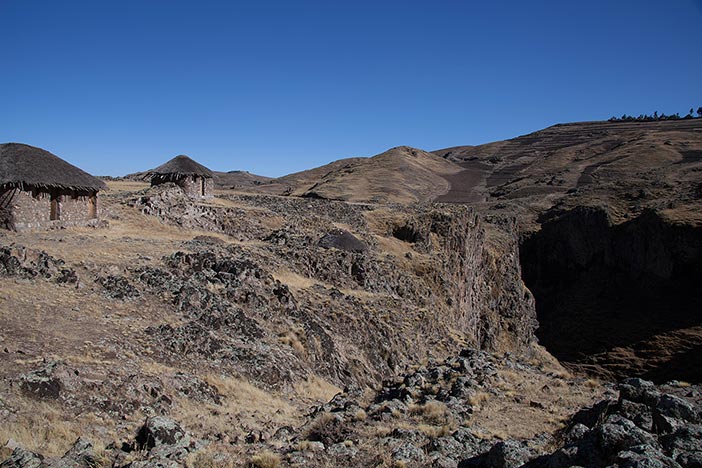

Ethiopia is beautiful. Dry, brown rolling hills morph into giant rock formations and canyons where sheep and hyenas roam. Stone huts, tukuls, with thatched roofs perch on cliff-tops, and the bustle of a market on a weekday morning can be heard from the mountainside.

I had planned a 5 day trekking trip with a local company where I would trek across the northern part of the country from Lalibela to Abuna Yosef mountain, one of the last places the Ethiopian wolf can be seen. It was a difficult trek, and I had been looking forward to it ever since I starting planning the trip in the small tour office in dusty Addis. The tour company stressed I wouldn’t be able to ride the donkey— the donkey was just for the bag and not for me. “Right,” I said at the time. Now I was trying to imagine someone riding such a comically small 4 legged creature as I watched the guides strap my duffel to its back.

The trip started well enough. I met my guide, Nathee, at the start point of the trek— a rural town where we ate a lunch of scrambled eggs (me) and mutton (Nathee), and plenty of injera; a tangy, soft Ethiopian bread. We started down a dusty trail along with two wizened old men who were the local guides.

Giant rock formations cropped up on either side of us as we hiked, and villagers with carts and donkeys passed on their way back from the market. Dust clouds rose up from my feet as we walked, it was dry season and the landscape looked parched. After several hours of hiking, steeps canyons rose around us, and we climbed steadily upward towards several stone tukuls perched on a cliff top in the distance.

As beautiful as the scenery was, I was a little nervous about my guide. Nathee was nice, he was informative, but he was a young guy and I was suspicious. I was waiting for the moment he would do something inappropriate and show some kind of interest and make it awkward. I was pleasantly surprised Nathee showed not the slightest interest in me save being a competent guide, and I silently chastised myself for having such little faith in people.

As we arrived in the camp, the giant canyon of Kurtain Washa unfurled below our feet. The tukuls were right at the edge of the cliff, one wrong move at night to the tukul that served as a toilet would sent you tumbling down into the abyss. I happily spent the rest of the day, to the amazement of the guides, clambering over the cliffside to hike through the canyon and climb up the steep rock faces that created it.

That evening, after sitting around a fire chatting with the local guides and sipping tea, I decided to head to bed. The next day would be 32 kilometers of trekking, and we needed to get an early start. Nathee had already shown me where I was to sleep. I had my own beautiful stone tukul, complete with two small beds overlooking the valley. As I got up to leave the fireside, Nathee offered to show me how to lock the door from the inside with large stones. I joked, “is this to keep the coyotes out?” The guides had already told me several stories about the coyotes at night.

“I can sleep with you if you like, if you’re afraid.”

I stared at him before responding, my heart sinking. “No… I’m not afraid. I was joking.”

“Let me get my stuff,” he replied, seemingly oblivious to my protests. “It’s crowded in there,” he added, gesturing to the main building where he was presumably going to sleep, all of 2 minutes before.

I numbly led the way to the stone tukul. I resigned myself to my fate and signed inwardly as I pulled my knife out of my duffel bag and slept with it underneath my pillow.

* * *

Waking early to an empty hut, I dressed quickly, grateful to be alone. Brushing my teeth outside on the edge of the cliff, I was pretty sure my toothpaste was biodegradable, but just in case I discreetly rinsed out my mouth around the side of the building. I headed back to my tukul to throw my toothbrush and dirty clothes in my duffel, then headed to the main building for breakfast.

The sun warmed my shoulders as I sat on a group of boulders, drinking tea and homemade bread with honey. Ethiopian honey is absolutely fabulous. I’ve never tasted the like of it since. It’s thick and cloudy and colored a delicate, pale yellow. The first time I tried it I exclaimed happily to one of the local girls who cooked the breakfast, who spoke no English, but smiled at my excitement of the breakfast food.

We set off for another day of hiking, the sky above bright blue with the moon still overhead in the sunshine. We hiked up steep ravines and across flatlands, stopping in a small Ethiopian school where the teacher shared his dreams of opening a small orphanage for the students who couldn’t afford to attend. The Ethiopian government was building schools all over the country, now that it offered free public education to every citizen. The problem was, orphans had to stay home and farm in order to grow food or make money to care for themselves, and had no time for school. He wanted to raise money to construct another building to house the students, and pay for their food and books for one year.

We stood outside, Nathee translating into English and the teacher speaking in Amharic. The children peered out the schoolhouse door at us, not quite sure what to make of the situation. The earnestness of the expression on the teacher’s face as he spoke to us outside that morning, his faced edged in the pale sunshine and the wind blowing around us, is ingrained in my memory. I will never forget the huge, empty feeling of the rolling hills, and the tiny schoolhouse, and the teacher standing beside it with such huge dreams. It struck me that he, being so passionate and dedicated with so little, changed so many lives while so many people who have everything, change nothing.

* * *

“They’ve never seen someone keep pace with us before,” Nathee told me, “They are impressed.”

We’d been hiking for 3 hours, and had just begun our descent over a mountain range, goats flowing around us making the trail precarious. I made sure to keep on the inside of the path, lest one of the goats give a head toss and send me tumbling over the edge.

“Really?” I asked.

Nathee recounted the group he had taken over the same pass the day before.

I tried to concentrate on the story as I made may way down the steep gravely path. I was wearing my hiking shoes of choice— the only pair of shoes I had aside from my beat up flip-flops. My beloved chucks, a 15 year old pair of Converse that were so lovingly worn they were completely smooth on the bottom. I hiked in them all the time, but at the moment, they were failing me.

I slipped and slided down the mountain path, the local guides gasping at the sound of every scrape of gravel, convinced I would fall. This did nothing to improve the situation. The journey down the mountain took 2 hours, and I was toe-holding every solid looking rock, essentially picking my way down the steep path. By the time we reached the bottom I was severely irritated with the guides and their molly-coddling, and had seriously pulled something in my right ankle.

Roughly 7 kilometers later, we arrived in a small town. Children and mothers alike emerged from their houses and fields as we passed through, shouts of Firengi! Firengi! (foreigner! foreigner!) echoing down the trail. We had been hiking throughout the hottest part of the day, and I was sweaty, and limping badly at a tortoise pace. I winced at every step, my ankle twanging painfully. I had developed blisters even on the bottoms of my feet, and the steep descent had created a dull, aching pain in both my knees.

We were still 10 kilometers away from the camp, I could see the tukul on top of the mountain in the distance, shimmering in the heat like some oasis in the dessert. I put my hand up to my forehead and squinted.

“How long do you think it will take to get there Nathee?”

“An hour and a half maybe? We made good time this morning.”

And on we went. The children in the villages ran up to us.

“Hello. Hello. Hello. Hello. Hello.” They followed me in groups repeating one word no matter what reaction I gave.

“Hello. Hello. Hello.” They followed us as we walked, sometimes far up the path. Nathee many times had to yell at them and shoe them away. For one particularly aggressive group of kids, he threw stones at them.

In my heart I knew they were proud of the English word they had learned. I knew they were excited to see a foreigner, and to try out the language they were being taught in school. In my heart I knew this. But I was in pain, every step was agony. I glared at them from behind my sunglasses. I thought angry, hateful thoughts. I was secretly glad Nathee had thrown stones at them, I wanted to throw stones at them myself. I was glad no one could hear my thoughts.

6 kilometers to go.

We stopped under a large tree on the side of the road. I took off my shoes and peeled of my socks. They were soaked. I realized as I inspected my feet they were bleeding. The donkey had wandered so far ahead, I had no way of getting a clean pair of socks or anything to wrap my feet up in.

3 kilometers to go.

A woman dressed in a flowing black skirt came up behind me carrying an umbrella. She fell into step with me, and held the umbrella over my head. It was such a simple act of kindness, I felt tears in my eyes. I was so miserable and wretched. Every step was agony, it was only sheer willpower that made me gone on. In the back of my mind I thought this is what climbing Everest must be like, only in the desert.

“Hello sister,” she said, “Don’t you have a sister, a friend in this country?”

I started crying. I actually started crying. I must have been the most pathetic sight; limping under the hot Ethiopian sun through the countryside. I have never been more grateful for sunglasses in my entire life. She walked with me for almost 2 kilometers before giving me a smile and swerving off the road into a building. Nathee double-backed and made a joke about the camp because 20 kilometers farther than he originally thought. He laughed like he had just made the funniest joke in the world.

I gave him a burning look of hatred.

* * *

By the time I had climbed up the mountain to where the camp was, I knew not only was I not going to be able to get down the mountain the next day to continue the trek, but I probably wouldn’t be able to for several days. I collapsed on the bed in my tukul, and lay there feeling miserable.

“Do you want a shower?” Nathee asked from the doorway. “They can boil water for you so it’s hot.”

“Yes please,” I gave him a weak smile.

“The shower is around front, no one walks there so it will be private.”

Let me explain about the showers at the camp. They are beautiful. They look like small wooden cages, open, exposed on all sides. They are not private.

The shower was on the other side of the main building at the camp, on a cliff, overlooking the town below. There is no way a reasonably attractive Firengi woman could get naked on a mountainside with no one noticing. I am not a modest person, but I will not openly strip where everyone can watch.

“Okay Nathee. A shower sounds great,” I replied.

“Amesegenallo,” I told the woman who brought me a bucket of water twenty minutes later. She also brought a smaller bucket with a cup to rinse with.

I stripped down to my sports bra and bikini bottoms, and sure enough, spotted several guides tending to donkeys on the other side of the camp, in full view. They weren’t looking my way, but I was glad not to be completely naked. A breeze blew over the side of the cliff, and I rinsed my hair looking over the side of the mountain, watching the activity in the town below. The sun cast an orange hue on the mountainside and the buildings in the town below. I could faintly hear the noise from the town, the sound of children playing and donkeys and the flour mill. As I sat there pouring bucket over bucket of water on my head, rinsing the last of the dust from my hair, I thought— this is one of the loveliest showers I’ve ever taken.

Under the pure blue Ethiopian sky, standing on a small wooden platform with aching feet, I found happiness in a bucket of lukewarm water and clean hair. I had everything I needed right here.

* * *

The next evening, sitting on one of the benches next to my tukul, enjoying another beautiful sunset, I contemplated the damage done to my legs. My right ankle felt sprained, probably from overuse. My left knee felt like I had pulled something somewhere. Both my feet were covered in an unfortunate amount of blisters which made wearing anything but flip flops impossible. Using my first aid training, earlier that day I had wound a compression wrap on my ankle and kept it elevated. I mused whether I would be able to climb down the mountain or not in a few days. All day long I had been hobbling around camp, barely able to walk, emerging from my tukul at mealtimes to drag my broken limbs up to the main building with the promise of food and the hope of more Ethiopian honey.

That afternoon, another traveler had arrived at camp, and we spent the evening with our guides singing songs in the communal room around a fire. Everyone was drinking but me, and I decided to head to bed early. As I hobbled back to my tukul under the light of the moon, my guide called to me from the doorway of the main building, then walked down behind me. He put a hand on my shoulder, “I’ll be joining you tonight,” he said. He was more than a little drunk.

“Why aren’t you staying in the main building like you have been?” I questioned, disbelievingly.

He muttered something incoherent and wandered off. Alarm bells were going off in my head. He could have mentioned this inside with everyone else at any point if this was a legitimate sleeping arrangement. But he didn’t. I considered locking the door of my tukul.

My level of comfort is gauged by how often I think of my knife. If I feel comfortable and safe in a situation, I don’t think of it at all. I fall asleep easily and wake up with nothing more on my mind than coming day and the sunrise. If I’m feeling unsure, I think of my knife frequently— where it is and how I can best reach it. I sleep with it under my pillow, arrange my sleeping position by how easily I can access it, and think of the best way to be on the offensive if someone were to try something.

As I climbed into my bed, my knife was on my mind.

I was reading my book when I heard the wooden door scraping across the floor of my tukul as it opened. Moonlight spilled into the room. Nathee entered and threw himself onto the bed opposite mine.

“What are you reading?” he asked.

“Nothing really, just a book,” I said curtly, trying to avoid conversation, and anything conversation might lead to.

“What’s it about?” he slurred, edging closer to my bed.

I sighed. “It’s a book about a kid who finds out he’s a wizard and goes to school. That’s about it.” How does one explain Harry Potter, honestly?

He got out of his bed and climbed on top of mine so he was lying next to me. “Show me,” he whispered in my ear, leaning in his head till it touched mine, hovering overtop me.

“Personal space!” I shouted.

“What?” he slurred, withdrawing slightly.

“What are you doing on my bed? And why are you sleeping in here anyway? This is not okay.” My frustration boiled over and exploded into indignation, and words. Who the heck just climbs into someone’s bed at night, without invitation? What was wrong with him?

“Sorry, sorry, so sorry,” he mumbled, as he grabbed his bag. “This is just like the first night.”

“On the first night, you didn’t get into bed with me.”

“Would you like me to sleep in the main room?”

“Yes I think that would be for the best.”

As soon as he left I bolted the door behind him.

I had come to think of my tukul as a sort of home, my private sanctuary on the mountain, and my guide, Nathee, had violated it. I hated that.

The first night I spent in Lalibela before the start of the trip, I didn’t leave my hotel. Every time I tried at least ten young Ethiopian men would come up to me and follow me to wherever I was going as soon as I left the gate. They would invite me places, share their names and introduce their friends. They were very nice, but it was exhausting. So I hid inside, stomach growling, reading my book. And being trapped on a mountaintop with someone who was my only company for the rest of the journey, someone else with expectations, made me sad.

I didn’t fall asleep for a long time.

* * *

The worst part about situations such as these, I thought to myself the next morning, is that they’re like one night stands without the good parts.

I couldn’t even look at Nathee the next morning at breakfast. I cheerfully greeted everyone and started up a conversation with the other traveler, while I contemplated how I was going to get down the mountain. I couldn’t spend another night there, not after the night before. The one other backpacker was leaving that morning, and I didn’t want to spend the night alone on the mountain with Nathee.

I was on the verge of cutting up some of my shirts for bandages when the other traveler offered up some extra compression bandages. With a walking stick, I might just might be able to get down the mountain with hopefully a minimum of pain. I winced as I tightened my beloved chucks around the compression bandage.

“Let me help you with that,” Nathee said, as he walked up to me as I sat on the outside bench.

“No thanks,” I replied. “I’ve got it.”

He looked at me for a moment, then sat down. “I think you’re angry at me for coming into your bed last night.” He looked at me hopefully.

I am nothing if not unfailingly honest. “Yes I am, but don’t mention it. Please.”

“You don’t have to leave, you can stay here another night.”

“No thanks, I’d really like to get back.”

He sat there for a minute, then walked off into the main building. He came back a few minutes later. “I didn’t know you were leaving today, so now we need to wait for the committee leader to come back from the village.” He had an air of irritation about him, like I was deliberately being problematic.

“We can catch the 12:30 bus back to Lalibela from the town,” I said, in a way of response.

After deliberations between the committee leader and Nathee, we were ready to descend the mountain into the village. It was painstakingly slow. But after agonizing concentration and following the incredibly steep and narrow mountain path, I reached the bottom where Nathee was waiting. Somewhere between the top of the mountain and the bottom he had decided to give me the silent treatment. Fine with me.

We grabbed an ancient bus back the rutted dirt road to Lalibela. It teetered precariously at the edges of steep ravines, and there was a close moment when a woman mimicked having to throw up and I had to grab my bags. After it dropped us off in the heart of Lalibela, I refused to pay the outrageous amounts the taxis were asking to get back to my hotel. Nathee acted like a wounded tiger until I told him he could leave and I would figure out my own way back. He left.

After re-routing my plane ticket to Capetown, South Africa, I chatted up a friendly Ethiopian and one of his friends gave me a lift back to my hotel. Traveler style.