Heading South: The Return of #FindingFitzRoy

Honduras

The sun is brilliant rising, warm oranges reaching from behind the mountains, touching the leaves on the trees and slowly making its way across the road. The pale shapes of the morning take form and become the highway, and I am no longer a shadowy thought but real, and present, and riding again, illuminated by the sun.

The empty road stretches into the green ahead, the mountains in the distance to my left. The cool wind blows over my shoulders and into the collar of my riding jacket, and every few minutes I glance behind to see the pink, golden rays of the sun.

***

Only the day before I had started riding again, loading up my bike in San Pedro Sula, the same straps and bags and gear, like I hadn’t been gone from this place an entire year, like the accident hadn’t happened. But it had. Eleven months earlier I had been hit outside this very town when a truck crossed the highway in front of me. He clipped my motorcycle and threw me across the road, breaking both bones in my right leg, tearing my leg open from left to right. Months after the accident I had vivid dreams where I’d wake up sweating, reliving riding down that same stretch of highway, the slow motion of the truck, the swerve, lying in the dust on the side of the road. The way it felt to lie alone in a dark corridor in the hospital bleeding, how it felt to sit in a wheelchair day after day, staring out the window. How hard it was to put one foot in front of the other and keep moving. After almost three months in a wheelchair, one month on crutches, and seven grueling months of physical therapy and gym sessions and recovery, I had flown back to San Pedro Sula to fix my motorcycle and continue my trip, heading south to Fitz Roy.

For the past three weeks in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, I had taken my bike from one place to the next— the machine shop to re-drill the oil filter cap that had been sheared off in the accident, the paint shop to repaint the fenders, and almost every government customs office in and around the city to sort out my overstayed temporary vehicle import permit.

At night I stayed at a tiny hostel in the hills of San Pedro Sula, and in the mornings Anthony— the grandfather of the Villanueva family who had stored my bike and used his connections to get me into surgery the year before— picked me up at my hostel and we’d drive around the city, slowly piecing together my bike. We’d stop by his home in the afternoon, where his wife Rafaela would be waiting with lunch. The second week, I thought I’d have to take the bus to Guatemala City to pick up a part that wasn’t available in Honduras. The third week, we discovered the fuel pump was bad.

I couldn’t clarify the mix of emotions pumping through my extremities. If I kept moving fast enough, I didn’t have to think about how I would feel when the bike was done, or what it would be like to start the engine and ride off down the road. I didn’t have to think about how it felt to roll across the highway and come to rest in the dirt. If I made lists of parts and costs and timeframes, of phone numbers and spanish translations, I could think about everything else later.

***

After three weeks, what seemed like forever and too soon all at once, my bike was ready. One afternoon, Antonio dropped me off at the Suzuki dealer, my motorcycle bags gathered in my arms. I threw a leg over the bike, and settled onto the seat. It was a pale grey day, the unremarkable kind that settles into the background. It was so hot my tank was soaked underneath my motorcycle jacket. I rested my hands on the handlebars, trying to make sense again of the way it felt, like coming back to a place years later I barely recognized. Key, safety switch, ignition. There was a loud buzzing in my head, so loud it seemed to drown out all the things I used to know and think about getting on the bike, it was louder than my own thoughts and made me fumble awkwardly every step.

My heart felt higher in my body than it ever had been as I slowly released the clutch and rode toward the busy intersection. I didn’t want to. Riding onto that busy street, I realized, was the last thing I wanted. Every part of me screamed not to, that it was wrong and dangerous and too loud, everywhere. The buzzing in my head and the sound of the cars, I could hear the thunk they made riding over the uneven surface, feeling every bump in my arms, every noise the sound of a rider being struck and scraped and thrown. I could feel the scar stretching around my right leg so much my leg started to hurt, and I noticed how frail and exposed it looked there, resting on the outside of my bike.

“It’s okay it’s okay it’s okay,” I whispered to myself over and over and over, as I released the clutch and accelerated into traffic. “It’s okay it’s okay it’s okay,” as I rode past an intersection where a giant truck had just t-boned a car. The carcass of the vehicle, now bent in half, rested on the curb. “It’s okay it’s okay it’s okay,” as I headed up into the hills. I stopped hearing the words I was saying— I could have been saying anything at the moment, it was the mantra I needed, the repetition of something to hold onto and focus.

I pulled into the drive at my hostel, turned off the engine, and crouched next to my bike, shaking. I wanted something, some sort of commemoration or swelling of music, some deep conversation that would end in character development and a new perspective— but it was just me. It was just me in the hot sunshine, standing next to the motorcycle I had spent weeks repairing, and the body that had spent eleven months working every day for this one.

***

Five years earlier I had learned to lead climb— the type of climbing with no attached rope at the top of the climb, but a series of carabiners leading up to the top where the climber would attach the rope as she climbed. When falling, she’d drop as far as the last place clipped in, further still depending on how much slack there was in the rope from the belayer.

One day, I was climbing with an friend to improve my lead climbing skills. “You need to practice falling,” he told me, “it’s the only way to not be afraid of the climb, to keep going.”

I climbed to the top of the wall, ending the route holding onto a large hold. “Let go,” he shouted.

And even though I didn’t want to, even though it felt wrong and dangerous and stupid, I let go of the hold, and leaned back into nothing. I fell fifteen feet before he caught me, my whole body lifting into the air as the rope caught. When my feet touched the mat again my legs were shaking, and even though there was nothing funny, I laughed. Years later I think about that moment— not what it felt like to fall but how it felt to start climbing again afterwards, knowing the drop was always there, waiting.

***

Honduras

Days before I left San Pedro Sula, an enormous eruption in Guatemala to the North-West left sixty-nine dead and hundreds injured, and simultaneously violence erupted in the neighboring country of Nicaragua to the South-East. It felt like Central America was imploding, and I was sandwiched in the middle with my motorcycle. The US Embassy in the capital city of Nicaragua was closed due to the unrest. The violent protests against the president, Daniel Ortega, had reached a peak, and it was rumored the border between Honduras and Nicaragua had been closed as well. Almost one hundred people had already been killed, and every day I watched the news as more violence erupted and scenes of people lying dead or being carried bloody in the arms of fellow protestors filled the news— first in Managua, then Masaya, then Granada. People ran through smoke filled streets wear masks and waving Nicaraguan flags and holding signs, while military police shot into crowds. Only the day before a man had been shot and killed trying to flee down the street on his motorcycle.

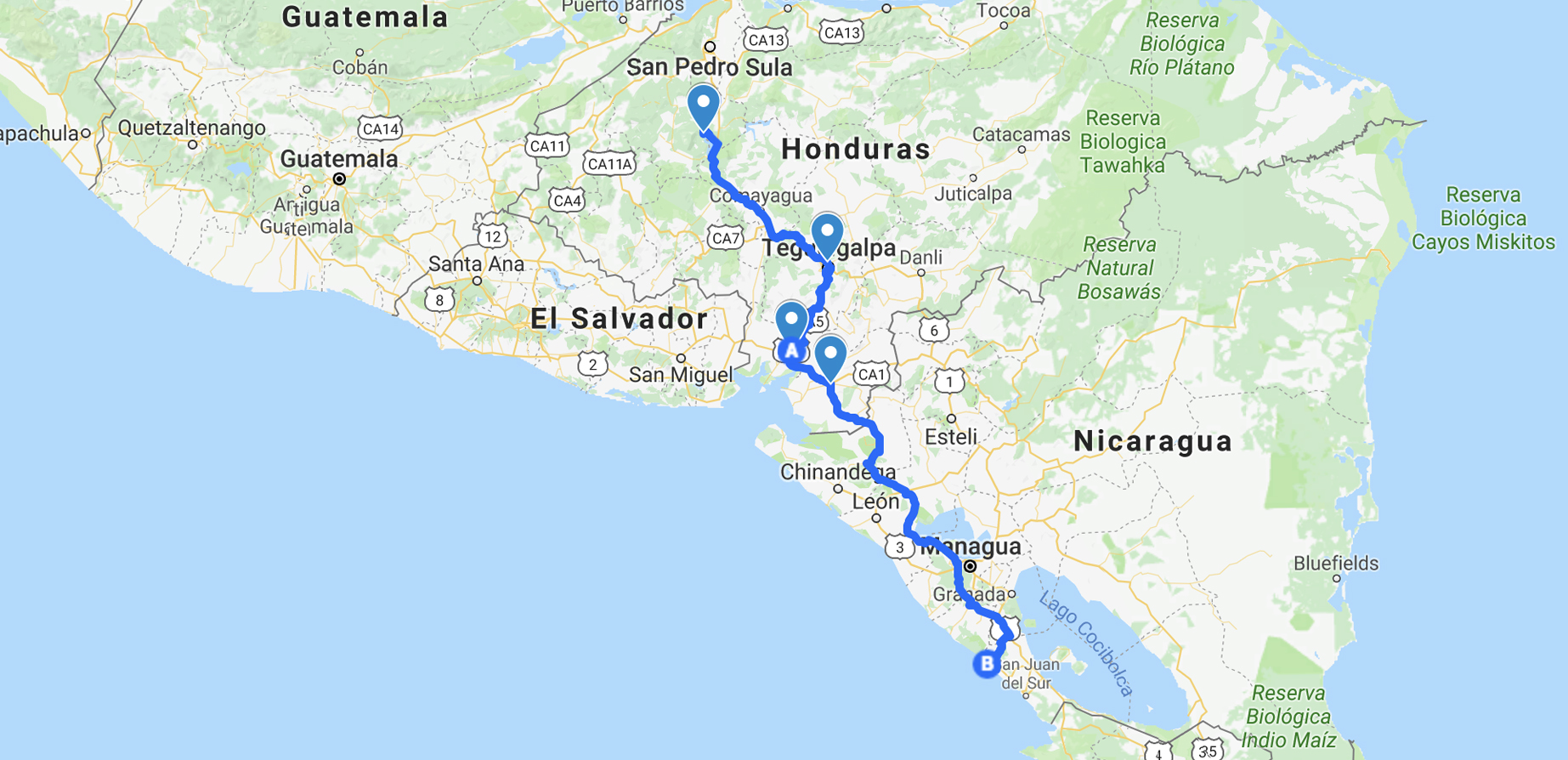

In just a few short weeks, what had started as a protest against Daniel Ortega for slashing social security and pensions had escalated into a potential civil war. Young people around the country erected roadblocks on all major thoroughfares to stop commerce, and it was rumored were willing to use violence on anyone who tried to pass. Small towns affected by the road blocks were running out of water and food and gas. Protests began erupting in farther flung places— Esteli in the North and Leon to the Northwest— right where I’d be riding through. For days I checked multiple sites, tracking the violence and planning the best route to cross the country. The day before I left, I wasn’t even sure I’d be able to cross the border. Since the popular bus line Ticabus was still running routes into Nicaragua from Honduras, I decided to go. I’d leave as early as possible at first light to cross the border into Nicaragua and ride through as much of the country as possible before dark.

***

Honduras

I woke half an hour before sunrise to load up my bike, outside the window everything one continuous shade of purple-grey. The sun had only just begun filtering through when I arrived at the Nicaraguan border. Inside, a woman heavily stamped my passport. “You know what’s going on right now don’t you?”

“I know,” I said, “I’m going to cross the country as quickly as possible.”

“Good luck, and be careful,” she said, sliding my passport back across the counter.

The roads quickly changed from disrepair to beautiful, flat stretches of black. It was exhilarating to accelerate on and on and on, without the heavy traffic and danger of debris and potholes. Riding in Honduras had been like an endless game of frogger, but Nicaragua was a fresh cool breeze, it was easy. The smooth empty highway snaked through the flat, green countryside in the sunshine, a tall volcano in the distance, smoke curling overhead. An hour after crossing the border I ran into my first roadblock. All of sudden, there was a line of trucks in my lane, stretching all the way into the distance. There were no brake lights, or smoke, or sounds of engines running— just a long, quiet line stretching on and on and on. It felt like a scene from an apocalyptic movie, where everything was too quiet, not another human in sight.

I accelerated into the left lane, passing one truck, then twenty. I could see something in the distance stretching across the road, what looked like a white wall. I caught up to another motorcyclist in front of me, and cautiously followed behind. We both slowed, and I realized what had looked like a wall was actually sandbags stacked high across the road, with a narrow passage in front of the left lane barely wider than a motorbike. A pile of packed sand lay in the pathway, and people in masks holding sticks and metal bars strode around the other side of the wall. A tuk tuk was trying to squeeze through the opening, its tires spinning in the sand, the other motorcyclist and I waiting behind it.

As soon as the tuk tuk was through, the other bike accelerated behind, maneuvering through the pile of sand and across to the other side. No one seemed to take any notice of me, and I held my breath as I quickly darted through behind the other motorcyclist, and accelerated into the right lane.

I rode for another two hours, crossing through the capital city of Managua without seeing roadblocks or violence. An hour outside the capital the road rose into the hills, and I started following another motorcyclist around the tight turns, the sky turning dark overhead. The air turned chilly, and a fog rolled in as we rounded a tight turn and the road ended in chaos.

Tractor trailers looked as if they had been thrown across the road, touching buildings on either side where people on foot squeezed through. Cars were abandoned in front of the trucks, forming haphazard, narrow walkways in between where people milled around. The smell of smoke was in the air, and a kind of electricity— like something was about to erupt.

There was no going back, and it looked like there was no going forward. I sat on my bike, watching the scene unfold.

“All of a sudden there was a shout, and the motorbikes around me erupted to life. The crowd of bikes surged forward toward the narrow opening in the sandbags.”

The motorcyclist in front of me rode up onto the steep curb where the sidewalk ended, and along the path I had seen people squeezing through from the other side. Up close, I could see a narrow footpath along the grass, the truck to the right, and to the left a steep drop down the hillside. He quickly maneuvered the bike around the sharp corner and disappeared. I sat there quietly for a split second. There was no turning back. I took a deep breath, and riding the clutch, leaned to the left and accelerated, hoping my pannier bags would clear the truck and not topple me down the embankment to my left. The bike bumped up and down, and I turned the front wheel to the right and leaned hard to the left as far as I could go without losing my balance and falling to the valley far below. A little more power. The rear wheel spun on the grass, and with a quick blip to the throttle I was back on the narrow path above the road.

I followed the motorcyclist for thirty minutes through the maze of trucks— it was the hardest riding I’ve ever done. He didn’t look back once, but always seemed to wait after each obstacle, then continue when I appeared behind him. My shoulders ached with keeping the bike upright, my stomach burning from leaning left then right, carrying the weight of the bike on my legs and arms. I rode down slippery grassy pathways, up steep curbs, down sidewalks scraping my turn signals on the tight passageways when there was barely enough room for a person to squeeze through, between the trucks and the buildings. I rode up a narrow slice of slippery tile the length of a truck, hardly daring to breathe as I balanced my bike on the sharp edge. Finally, after squeezing between an abandoned storefront and a truck to my left, there was the last section of the roadblock in front of us— a low wall of white sandbags. Motorcycles were parked everywhere, and groups of people in masks shouted and ran the length of the sandbag wall, higher than the last one. The smell of something recently burnt hung in the air, and smoldering ashes lay on the pathway through the roadblock.

“This is the moment where something serious happens,” I thought to myself, as if this weren’t serious enough. I inched forward toward the passageway, pulsing the throttle, every inch of me alert. I had no idea what to expect— I was obviously a gringa, in my all black riding gear and bright orange motorcycle with a foreign plate, my blonde hair in a braid slung over one shoulder.

There was so much life, and shouting, flags waving overhead and people perched on the beds of trucks. I was surrounded by motorcycles, motorcycles parked along the edges in front of semis, motorcycle squeezing into the spaces around I hadn’t noticed until our elbows were almost touching. All of a sudden there was a shout, and the motorbikes around me erupted to life. The crowd of bikes surged forward toward the narrow opening in the sandbags. Suddenly, a man sitting on a platform next to the wall shouted, “Gringa! Gringa!” pointing at me.

A group of men sitting on a truck platform turned to me with shouts, “Hermosa! Guapa!” The man at the front threw his arms wide with a huge smile and started blowing me kisses and waving wildly. Heart pounding, I inched through the narrow sandbag passage over piles of ashes to the chorus of ‘beautiful!’ and blown kisses.

View this post on Instagram

***

One Year Earlier, San Pedro Sula

I lay in an empty metal van, bouncing up and down over speed bumps that lined the road, potholes jostling my body, blood running down my leg underneath a dirty dish towel covering the open bone. My back was raw and bleeding from being scraped across the asphalt, small pebbles coating the raw, bleeding skin.

A woman was in the van with me. She had climbed in the bed of the truck at the accident, and again when I was transferred to the van— two men sliding me into the back on a simple, canvas stretcher. She was carrying the bags from my motorcycle and my helmet, and had stuffed my passport down her shirt to keep it safe. “You never know who to trust,” she told me, as she held my hand. She held my hand when they unloaded me at the public hospital, and again when they were setting the bone while young interns bustled around me. I was shaking— the room didn’t seem real, like I was watching a slow motion film that shook at the edges, but I could feel the weight of her fingers around mine.

I found out later she was a passenger in the truck that hit me— her brother had been driving. The whole time, she knew. She knew her brother was responsible, she must have felt the weight of my motorcycle hit the truck, seen me thrown across the highway.

Whatever her motives, she didn’t have to be there, watching over my bags and keeping my passport safe, talking with the doctors and offering to help in any way she could. In all the eleven months I spent recovering, it was this woman— a stranger who in a distant way held some responsibility for the accident— who held my hand.

***

Nicaragua

The road was on fire. Uneasily, the other motorcyclist and I glanced at each other. Smoke billowed 100 feet away where a giant truck was jackknifed across the road, a crowd of people shouting and circling it as great flames rose up to touch the smoke above. We’d been riding together for a few hours, and now, we were trapped between the enormous roadblocks and the flames ahead. We sat there in silence, unsure how to proceed, stopped in the middle of the lane some distance away from the flames.

Slowly, cautiously, we both rode forward. When we got closer, we saw it wasn’t the truck that was on fire but giant palm fronds aflame in the road. A pile of glowing red embers lay scattered around the dying fronds in front of a group of people in masks. Through the smoke, we could see cars waiting on the other side, unknowing the road was completely blocked in the other direction.

After a few minutes, the people in masks cleared the palm fronds, and gave a signal for us to ride thorough. Smoke surrounding us, I held my breath as the flames licked the ground to my right. The smoke burned my eyes, and I slowed to ride behind the glow of the taillight of my fellow rider, passing the long snake of cars to the left.

“In the violence erupting around us, those small acts of human kindness are what I remember most. Moments that on their own were tiny and delicate, but filled my heart with the brightest golden light.”

There was no gas. Gas stations were roped off with caution tape, people were everywhere in the streets. I rode through small towns where military police watched the road blocks from a distance, arms folded. I rode past lines of cars stretching miles and miles, motorcycles riding directly at me in the opposite direction, the only way through the roadblocks.

It seemed there was always someone riding with me, even after my fellow motorcyclist and I parted ways. For a time, it was a man and a small boy, then a group of motorcyclists riding down the same deserted stretch of highway. I stopped at one point to adjust my tank bag, and a motorcyclist I had been riding with for some time circled around to wait for me, and then we continued. Without saying a word, we were all riding south together, and would wait for each other to move on. In the corruption and violence erupting around us, those small acts of human kindness are what I remember most. Moments that on their own were tiny and delicate, but filled my heart with the brightest golden light.

***

I arrived in Popoyo 11 hours after I started riding from Honduras early that morning. The last two hours were down a muddy, dirt road in which I made two river crossings, unloading my motorcycle and slopping through knee high water carrying my bags across before returning to ride my bike through.

I arrived to the most brilliant white sand beach and perfect, arcing blue waves, soaked and exhausted and covered in mud. I stayed for one week on that coastline, listening to the news and talking with locals about the government and violence and dwindling supplies in the small towns on the coast. At the end of the week, I bought gas from couple on the side of the road just outside of town, chickens flocking around my bike. The man filled my gas tank from an old 2-Liter Coke bottle filled with gasoline. It didn’t quite fill the tank, but would get me across the border to Costa Rica where there would be gas.

Nicaragua

I rode out of Popoyo at 5 AM on a Saturday, my body leaner and stronger than it had been the week before, the dirt road completely empty, the ocean waves crashing on one side and the sound sitting quietly on the other.

It wasn’t without cost, this freedom to ride a motorcycle down a remote road in Central America at dawn, to watch the sun rise and feel the wind. How easily it could be taken away, but how appreciative I was of it then, how delicate and fierce life could be at the same time. I rode on, up hills and through valleys, winding along to distant places, leaving behind the woman I had been last year, before the accident. I could remember her, if I tried, like trying to see a room by candlelight— glimpses through the darkness. The longer I rode the less real she became, until there was only one of us, and I rode on.

Read more about #FindingFitzRoy here.