In Which I am Almost Swept Out to Sea, Make Bad Choices, and am Lost in a Sea of Shrubbery

Memoirs from Ecuador: for many years I’ve made regular trips to the town of Montañita on the Ecuadorian coast, and have had many, many adventures there. Some good, some bad, some strange. These are my stories.

2017

The cottage stood on a small hill next to a sandy path that led down to the sea. Low bushes met the sand and ran in a line between the shore and the start of scrubby inland grasses, and although they created a natural wall directly in front of the cottage, I could hear the waves all night long.

To the right lay the Point and the small town of Montañita, small dots of light and the echoes of discotecas floating across the distance at night. To the left a river that divided the Kamala area, where my cottage lay, and the town of Manglaralto. Just behind the river, a concrete pathway led around the river and along the beach, cupping the town of Manglaralto in its cradled elbow.

I found the cottage by accident one afternoon, the listing popping up on AirBNB— a simple cottage for $20 a night, with two donkeys in the next field, and Kamala Backpackers hostel right next door where I could make use of the facilities and, park my motorbike just inside its gate. When I arrived, the property manager, an older man who was nice enough but overly attentive in a slightly lecherous way gave me a tour of the cabin that had been recently vacated by a young Australian man who, by the looks of it, hadn’t cleaned the place once in his 6 month stay. The bathroom stank of urine, and perched next to the toilet sat a large piece of slate, coated in ash and a pile of joint stubs.

The cottage was a small A-frame— the joints made of bamboo, meeting in a tall point that could be seen from the beach and covered with a thatched roof made of palm fronds. The inside walls were made of bamboo walls, and the floor wide-wooden planks painted a dark brown, the edges flaky. A double bed sat in the corner under the sloping roof, mismatched sheets with a round mosquito netted knotted above it and a single bed opposite tucked under the steepest part of the roof. The bathroom featured a tiny wooden door that left gaping cracks of light when closed at night that opened up into a narrow yellow passage with a toilet and sink and a small wooden stool I used to pile my bobby pins, hair ties and moisturizer. At the back of the passage another door opened up into a large, round circular shower made of stones and bamboo for the walls, where I would frequently peer out between its cracks expecting the property manager to be somewhere close-by. The shower was surrounded by a small garden of plants and accented with a flowered plastic curtain that also functioned as a door separating the outdoor shower from the outdoor kitchen. The outdoor kitchen completed a circle that led back to the front door, the outside area floor made up of a dry, sandy red brick. Hovering over the front door was a rickety wooden structure that functioned as a lookout, where a series of battered wooden steps led up to the platform, nails popping out of every board, the structure swaying with each step where two moldy plastic chairs sat on top with a beautiful view of the waves and coastline stretching from Montañita all the way to Manglaralto. Pelicans soared overhead.

The property manager handed me the key to the cottage which fit a padlock on the front door. Peering into the cottage for one last check to make sure I had everything, I noticed a strange lump on the inside of the A-frame, under a thin piece of fabric that stretched across the bamboo, separating the inside of the cabaña from the underside of the roof. The lump appeared to be moving slightly. I looked at the property manager. He leaned over and poked it with his finger. It squealed and readjusted itself.

“What,” I asked, “is that?”

“Zarigueya.” He grunted. A possum. And with that the property manager dropped my motorcycle bag inside the doorway of the cottage, told me he would be back to clean (he wouldn’t), and that was that.

***

I spent the first afternoon in the cottage scrubbing the bathroom which took an entire gallon of bleach and a sponge worn down to nothing after I had finished, which I promptly threw into the trash. I swept a mountain of sand from the inside floors, opened all the doors and windows to air out the place, organized the small collection of rusty pots in the outdoor kitchen where a family of spiders had taken up residence, and folded my clothes neatly on the spare bed that would function as my wardrobe. The small gate to the cottage open as I swept sand from the warm bricks into the yard, a large white man with a shaved head approached me from the field. He introduced himself as Stan, my neighbor, and promptly began a long-winded monologue about Christ, and how alligators are the devil’s animals.

I piled my motorcycle bags and helmet in the front corner of the house under the window, and hung my backpack on a small hook inside the door. It was simple, but it was home— for now.

***

Every night, I fell asleep in the dark with the moon overhead and possums scuttling over the thatched roof, dropping to the grass outside every so often with a loud thump. Every morning, I opened the small gate to my cottage, and walked down a tiny sandy path to the sea. It was a tunnel of green that opened up to the great expanse of shore stretching far in either direction, the even light of a cloudy morning illuminating the edges of the waves gently rolling in and breaking in a cloud of foam just offshore. I tied the padlock key to the laces of my running shoes, and began running towards Montañita— past the graffitied ruins of what was once a shrimp laboratory destroyed by a storm, past seemingly abandoned small hotels on the beachfront, lush vegetation sprouting up between small houses and hotels, small crabs hastily scuttling sideways into the holes at the sound of my pounding feet. Sometimes, there were treasures left on shore by the waves in the night. A needlefish, an overturned horseshoe crab, baby turtles, blue bottle jellyfish and, once, the carcass of an enormous Galapagos sea turtle.

I ran past the malecón, large dark gray boulders lining the beach where small flights of stairs led up to the concrete path where beachgoers could watch the waves and take selfies at the iconic Montañita sign— a large surfboard with ‘Montañita’ spelled out alongside. At high-tide the waves would arrive all the way up at the foot of the malecón, and I loved running there when the tide was coming in, sandwiched between the wall of rock and the waves, sprinting across that section of the beach, the foam chasing my heels. I ran toward the Point, at the very end of Montañita, a rocky outcrop with tidepools that jutted out to the sea and sported a tall rock formation with a point on top. Rumor was an expat had bought the land many decades ago, and recently, the township ‘couldn’t find’ the paperwork supporting the purchase, claiming it was never filed correctly.

I ran almost to the Point, turned around, and ran back to Montañita, pausing to run up a small street sandwiched between two discotecas— Poco Loco and Lost Beach Club. The gray brick-lined street ended at a one-way street closed off to traffic (save the occasional motorcycle selling limes or fruit or Bolón) lined with small carts and brightly colored parasols. One of the carts at the end was run by the Flores family— three sisters, who were one of the first families to settle in Montañita before it became a famous surf destination. Every morning I sat and gossiped about the town, which was usually some sort of horrific thing or another that had occurred that weekend or in the weeks before. Gang violence in the street, a rumor about how Venezuelan refugees had eaten all the town iguanas, which surfista had drugged a tourist drink and raped her, someone who had recently been killed at Hidden House Hostel— a spot well know for its parties and locally known for its skeezy owner who frequently covered up numerous sexual assaults, overdoses, and even deaths that occurred on the property. Once, it was a story about two local men who waited for a woman who ran regularly on the same beach, and they had set a trap for her, hiding a line of cable in the ground, then attacked her— but she got away. No charges were ever brought against the town because, in the pueblo’s words, it was “her word against theirs and there was no proof”. Sometimes it was harmless gossip, sometimes it was gang violence, sometimes it was a problematic neighbor who liked to urinate on my friend’s food stall late at night in protest (of what I’m not sure).

We chatted and Tanya, the oldest of the sisters who had become a friend over the years, would make me a juice. Maracuya (passion fruit) and mango and fresa (strawberry), kiwi and fresa, piña and mango. I’d sit on a small plastic chair next to the cart watching them make crepes and pancakes and sandwiches and juices for tourists and we’d chat for an hour or so, and then I’d run back to the cottage in what was now a hot and humid morning with the sun peering through the clouds.

***

One night, cozy in my cottage listening to the waves and reading a book, I decided to walk over to Manglaralto for something to eat. I walked through what was now a black tunnel onto the beach, the ocean and beach black save for a yellow glow in the distance and pockets of stars in the sky overhead. In the distance, another sound rose out of the dark, a powerful rushing sound that wasn’t the ocean. I arrived at the river to find it rushing out to sea in the outgoing tide. What was a mild trickle during the day had risen, and now a small dark river had taken its place, angrily rushing out to sea. I had my camera and my phone in my backpack, and debated the wisdom in crossing a dark river on the beach at night, with the possibility of being swept out to sea.

***

When I was younger, every summer my family and I would go to the Outer Banks in North Carolina, a popular beach destination on the East Coast in the States that also happened to be a long treacherous island chain. The Outer Banks used to be a haven of pirate activity and shipwrecks due to the ever changing coastlines, currents, and shifting ocean floor. It’s now a popular spearfishing and diving spot, and the tops of shipwrecks can be spotted at low tide, masts peering out from their watery graves below.

I was fascinated by the diagrams of rip currents that were always posted in the rental houses we stayed at, red arrows clearly showing how to spot the riptides and how to swim out of them, the swimmer a tiny line-drawing amongst the waves and currents. I loved to see the red flags flying at the beach on stormy days, and try to spot the telltale rip currents in the water— the muddy water a long current, the waves breaking in a strange manner, the stream of foam. I’d sit on the shore in the wind, and try to spot all the danger zones along the shore, the places that were treacherous but so hard to see on the surface.

***

I stepped out of my flip flops and held them in one hand above my head, the small sand cliff crumbling at my feed, clumps of sand dropping into the dark below. When a river dumps out into an ocean with the outgoing tide, it creates a bank on either side— there’s no way of ‘testing’ how deep the water is first, especially in the dark. I jumped into its yawning mouth.

The water came up past my thighs, soaking my shorts— it pushed against my legs, rushing in streams of foam that seemed alive and soulless at the same time in its relentless movement and quest to reach the sea. I leaned into the oncoming water and struggled forward in the soft sand, hoping this was the deepest part. After a few minutes I pulled myself from the current, clambering up the sand bank toward the quiet yellow lights of the malecón in Manglaralto, soaked and sweating in the dark.

***

One unfortunate evening, I was perched on a wooden stool working on my laptop at the bar in Kamala Backpackers when my laptop mysteriously shut down, in the middle of a project for a client that was due that week. It wasn’t the first time electronics had malfunctioned in Montañita. My old laptop had mysteriously died in the humid climate, but was an older model I could easily open up and reset the RAM (which I did one day, crouched over the bones of the laptop on the wooden front porch of my tiny cabaña).

On my phone, I found a shop that repairs Apple products in Guayaquil, the main port city three hours away by bus. I made an appointment for the next day and made a plan to get up early and call for a taxi from the hostel front desk. The next morning I woke up just before dawn, packing my laptop in my backpack. I padlocked the front door of my cottage, opened and closed the small front gate, and set off across the field to the Kamala hostel restaurant and office where the two donkeys (and probably my crocodile-fearing neighbor) watched me with wary eyes.

It was raining, which I had not anticipated, which in turn had caused the WiFi to go out during the night. I arrived at Kamala damp and sliding in the mud, offline, making my way up the low grassy hill which had turned into a muddy slope overnight. When I arrived at the restaurant, I found everything boarded up and the office closed. No one was there to call a taxi or reset the WiFi, and probably wouldn’t be for another few hours.

It’s important to note, while lovely and rustic, my cottage was not close to anything save a pair of donkeys and the empty beach. It was down a long dirt road, a 20 minute walk from the town of Montañita, and a 10-15 minute walk and river crossing to Manglaralto. I could walk to the main road, but that was another 15 minute walk perpendicular to the beach along a muddy dirt road. I had no WiFI, no means of calling a taxi, and it was raining and I had my laptop in my bag. My motorcycle didn’t have great tires for riding down slippery, muddy roads, and even if it did, there wasn’t a place in town I could safely leave it for an entire day. I weighed my options, and decided to walk down to the beach in hopes I could cross the river and walk to Manglaralto to the main road and catch the early bus to Guayaquil.

I arrived on the beach, and with the addition of the rain and the outgoing tide, the river was now roaring out to sea. A long rip current stretched out deep into the sea, the color of mud. It wasn’t worth the risk, even without my laptop. I contemplated walking back up past Kamala to the road, but since Manglaralto was so close, perhaps there was a quicker path through the scrubby bush that lined the river. I had often seen people appearing on this path making their way to the beach.

I set off up the muddy path, my feet siding in the mud. The path went for a little way into the scrubby bushes, then suddenly ended in an expanse of shrubs and muddy sand, close to where I had once spotted a diseased and emaciated possum. The river to my right, dense bushes to my left, I staggered on hoping at some point I would meet up with the road. As it dawned on me I had probably made an ill-advised decision entering what now seemed now like a grassy wasteland instead of taking my chances with the muddy but known stretch of road, I slipped and fell into the mud. For some time afterwards I flailed around in the shrubs, going one way and then the next, lost in a sea of brittle grass, pouring rain, and shrubbery somewhere between the overflowing river, the sea, the main road, and Kamala Backpackers. I finally emerged at the main road 25 minutes later, covered in twigs and dirt and completely soaked. I walked briskly down the main road in the rain which began to fall even faster, arriving at the La Libertad bus stop a few minutes later to hop on the bus and sit for three hours in the freezing air conditioning in the wet clothes, clutching my backpack with my laptop inside like a shipwreck survivor.

***

I arrived at the bus station in Guayaquil a little over three hours later, ran through the enormous terminal to the taxi line, took the taxi to the iShop, and waited covered in dried, flaking mud in the carpeted office where I explained the situation and was told I could come back tomorrow and pick up my laptop first thing. Not anticipating an overnight stay, and not wanting to go back to Montañita only to return the next morning, I spent the night in Guayaquil at a cheap hotel I liked called Atlantic Suites. Still in my muddy clothes, I used the tiny bar of cheap lavender soap to take a shower and clean the mud out of my clothes, and slept naked on top of the crunchy quilted blanket, dreaming of the sea.

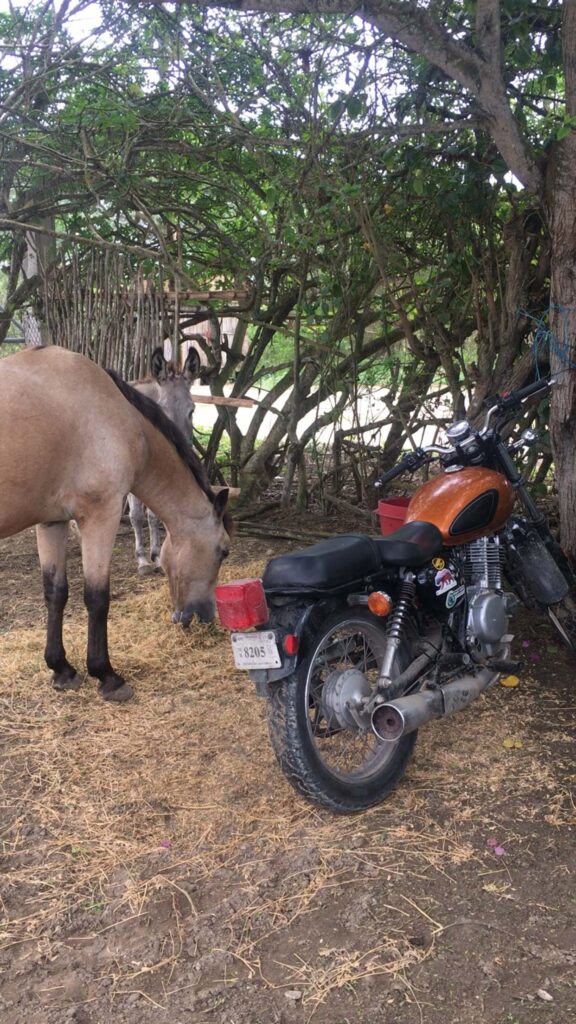

- The cottage and my motorcycle.

- The road to Kamala.

- The cottage.

- Needlefish on the beach in the morning.

- Sunsets from the beach.

- View from the lookout in the cottage.

- The Flores cart, many years ago.

- The remains of the shrimp laboratory.

- Lunches at the outdoor kitchen in the cottage.

- Sunsets.

- Pelicans flying over the cottage.

- The outdoor kitchen at the cottage at night.

- Pie de Limón on the lookout at the cottage.

- Reading.

- Montañita years ago when all the roads were dirt.

- Books.

- Tanya and breakfast alley.

- The donkey.

- Sunset from the lookout at the cottage.

- The parking spot.

- The outdoor shower.

- Running route.

- The lookout at the cottage.

- Neighbors.