In Which I am Almost Swept Out to Sea, Make Bad Choices, and am Lost in a Sea of Shrubbery

Memoirs from Ecuador: for many years I’ve made regular trips to the town of Montañita on the Ecuadorian coast, and have had many, many adventures there. Some good, some bad, some strange. These are my stories.

2017

The cottage stood on a small hill next to a sandy path that led down to the sea. Low bushes met the sand and ran in a line between the shore and the start of scrubby inland grasses, and although they created a natural wall directly in front of the cottage, I could hear the waves all night long.

To the right lay the Point and the small town of Montañita, small dots of light and the echoes of discotecas floating across the distance at night. To the left a river that divided the Kamala area, where my cottage lay, and the town of Manglaralto. Just behind the river, a concrete pathway led around the river and along the beach, cupping the town of Manglaralto in its cradled elbow.

I found the cottage by accident one afternoon, the listing popping up on AirBNB— a simple cottage for $20 a night, with two donkeys in the next field, and Kamala Backpackers hostel right next door where I could make use of the facilities and, park my motorbike just inside its gate. When I arrived, the property manager, an older man who was nice enough but overly attentive in a slightly lecherous way gave me a tour of the cabin that had been recently vacated by a young Australian man who, by the looks of it, hadn’t cleaned the place once in his 6 month stay. The bathroom stank of urine, and perched next to the toilet sat a large piece of slate, coated in ash and a pile of joint stubs.

The cottage was a small A-frame— the joints made of bamboo, meeting in a tall point that could be seen from the beach and covered with a thatched roof made of palm fronds. The inside walls were made of bamboo walls, and the floor wide-wooden planks painted a dark brown, the edges flaky. A double bed sat in the corner under the sloping roof, mismatched sheets with a round mosquito netted knotted above it and a single bed opposite tucked under the steepest part of the roof. The bathroom featured a tiny wooden door that left gaping cracks of light when closed at night that opened up into a narrow yellow passage with a toilet and sink and a small wooden stool I used to pile my bobby pins, hair ties and moisturizer. At the back of the passage another door opened up into a large, round circular shower made of stones and bamboo for the walls, where I would frequently peer out between its cracks expecting the property manager to be somewhere close-by. The shower was surrounded by a small garden of plants and accented with a flowered plastic curtain that also functioned as a door separating the outdoor shower from the outdoor kitchen. The outdoor kitchen completed a circle that led back to the front door, the outside area floor made up of a dry, sandy red brick. Hovering over the front door was a rickety wooden structure that functioned as a lookout, where a series of battered wooden steps led up to the platform, nails popping out of every board, the structure swaying with each step where two moldy plastic chairs sat on top with a beautiful view of the waves and coastline stretching from Montañita all the way to Manglaralto. Pelicans soared overhead.

The property manager handed me the key to the cottage which fit a padlock on the front door. Peering into the cottage for one last check to make sure I had everything, I noticed a strange lump on the inside of the A-frame, under a thin piece of fabric that stretched across the bamboo, separating the inside of the cabaña from the underside of the roof. The lump appeared to be moving slightly. I looked at the property manager. He leaned over and poked it with his finger. It squealed and readjusted itself.

“What,” I asked, “is that?”

“Zarigueya.” He grunted. A possum. And with that the property manager dropped my motorcycle bag inside the doorway of the cottage, told me he would be back to clean (he wouldn’t), and that was that.

***

I spent the first afternoon in the cottage scrubbing the bathroom which took an entire gallon of bleach and a sponge worn down to nothing after I had finished, which I promptly threw into the trash. I swept a mountain of sand from the inside floors, opened all the doors and windows to air out the place, organized the small collection of rusty pots in the outdoor kitchen where a family of spiders had taken up residence, and folded my clothes neatly on the spare bed that would function as my wardrobe. The small gate to the cottage open as I swept sand from the warm bricks into the yard, a large white man with a shaved head approached me from the field. He introduced himself as Stan, my neighbor, and promptly began a long-winded monologue about Christ, and how alligators are the devil’s animals.

I piled my motorcycle bags and helmet in the front corner of the house under the window, and hung my backpack on a small hook inside the door. It was simple, but it was home— for now.

***

Every night, I fell asleep in the dark with the moon overhead and possums scuttling over the thatched roof, dropping to the grass outside every so often with a loud thump. Every morning, I opened the small gate to my cottage, and walked down a tiny sandy path to the sea. It was a tunnel of green that opened up to the great expanse of shore stretching far in either direction, the even light of a cloudy morning illuminating the edges of the waves gently rolling in and breaking in a cloud of foam just offshore. I tied the padlock key to the laces of my running shoes, and began running towards Montañita— past the graffitied ruins of what was once a shrimp laboratory destroyed by a storm, past seemingly abandoned small hotels on the beachfront, lush vegetation sprouting up between small houses and hotels, small crabs hastily scuttling sideways into the holes at the sound of my pounding feet. Sometimes, there were treasures left on shore by the waves in the night. A needlefish, an overturned horseshoe crab, baby turtles, blue bottle jellyfish and, once, the carcass of an enormous Galapagos sea turtle.

I ran past the malecón, large dark gray boulders lining the beach where small flights of stairs led up to the concrete path where beachgoers could watch the waves and take selfies at the iconic Montañita sign— a large surfboard with ‘Montañita’ spelled out alongside. At high-tide the waves would arrive all the way up at the foot of the malecón, and I loved running there when the tide was coming in, sandwiched between the wall of rock and the waves, sprinting across that section of the beach, the foam chasing my heels. I ran toward the Point, at the very end of Montañita, a rocky outcrop with tidepools that jutted out to the sea and sported a tall rock formation with a point on top. Rumor was an expat had bought the land many decades ago, and recently, the township ‘couldn’t find’ the paperwork supporting the purchase, claiming it was never filed correctly.

I ran almost to the Point, turned around, and ran back to Montañita, pausing to run up a small street sandwiched between two discotecas— Poco Loco and Lost Beach Club. The gray brick-lined street ended at a one-way street closed off to traffic (save the occasional motorcycle selling limes or fruit or Bolón) lined with small carts and brightly colored parasols. One of the carts at the end was run by the Flores family— three sisters, who were one of the first families to settle in Montañita before it became a famous surf destination. Every morning I sat and gossiped about the town, which was usually some sort of horrific thing or another that had occurred that weekend or in the weeks before. Gang violence in the street, a rumor about how Venezuelan refugees had eaten all the town iguanas, which surfista had drugged a tourist drink and raped her, someone who had recently been killed at Hidden House Hostel— a spot well know for its parties and locally known for its skeezy owner who frequently covered up numerous sexual assaults, overdoses, and even deaths that occurred on the property. Once, it was a story about two local men who waited for a woman who ran regularly on the same beach, and they had set a trap for her, hiding a line of cable in the ground, then attacked her— but she got away. No charges were ever brought against the town because, in the pueblo’s words, it was “her word against theirs and there was no proof”. Sometimes it was harmless gossip, sometimes it was gang violence, sometimes it was a problematic neighbor who liked to urinate on my friend’s food stall late at night in protest (of what I’m not sure).

We chatted and Tanya, the oldest of the sisters who had become a friend over the years, would make me a juice. Maracuya (passion fruit) and mango and fresa (strawberry), kiwi and fresa, piña and mango. I’d sit on a small plastic chair next to the cart watching them make crepes and pancakes and sandwiches and juices for tourists and we’d chat for an hour or so, and then I’d run back to the cottage in what was now a hot and humid morning with the sun peering through the clouds.

***

One night, cozy in my cottage listening to the waves and reading a book, I decided to walk over to Manglaralto for something to eat. I walked through what was now a black tunnel onto the beach, the ocean and beach black save for a yellow glow in the distance and pockets of stars in the sky overhead. In the distance, another sound rose out of the dark, a powerful rushing sound that wasn’t the ocean. I arrived at the river to find it rushing out to sea in the outgoing tide. What was a mild trickle during the day had risen, and now a small dark river had taken its place, angrily rushing out to sea. I had my camera and my phone in my backpack, and debated the wisdom in crossing a dark river on the beach at night, with the possibility of being swept out to sea.

***

When I was younger, every summer my family and I would go to the Outer Banks in North Carolina, a popular beach destination on the East Coast in the States that also happened to be a long treacherous island chain. The Outer Banks used to be a haven of pirate activity and shipwrecks due to the ever changing coastlines, currents, and shifting ocean floor. It’s now a popular spearfishing and diving spot, and the tops of shipwrecks can be spotted at low tide, masts peering out from their watery graves below.

I was fascinated by the diagrams of rip currents that were always posted in the rental houses we stayed at, red arrows clearly showing how to spot the riptides and how to swim out of them, the swimmer a tiny line-drawing amongst the waves and currents. I loved to see the red flags flying at the beach on stormy days, and try to spot the telltale rip currents in the water— the muddy water a long current, the waves breaking in a strange manner, the stream of foam. I’d sit on the shore in the wind, and try to spot all the danger zones along the shore, the places that were treacherous but so hard to see on the surface.

***

I stepped out of my flip flops and held them in one hand above my head, the small sand cliff crumbling at my feed, clumps of sand dropping into the dark below. When a river dumps out into an ocean with the outgoing tide, it creates a bank on either side— there’s no way of ‘testing’ how deep the water is first, especially in the dark. I jumped into its yawning mouth.

The water came up past my thighs, soaking my shorts— it pushed against my legs, rushing in streams of foam that seemed alive and soulless at the same time in its relentless movement and quest to reach the sea. I leaned into the oncoming water and struggled forward in the soft sand, hoping this was the deepest part. After a few minutes I pulled myself from the current, clambering up the sand bank toward the quiet yellow lights of the malecón in Manglaralto, soaked and sweating in the dark.

***

One unfortunate evening, I was perched on a wooden stool working on my laptop at the bar in Kamala Backpackers when my laptop mysteriously shut down, in the middle of a project for a client that was due that week. It wasn’t the first time electronics had malfunctioned in Montañita. My old laptop had mysteriously died in the humid climate, but was an older model I could easily open up and reset the RAM (which I did one day, crouched over the bones of the laptop on the wooden front porch of my tiny cabaña).

On my phone, I found a shop that repairs Apple products in Guayaquil, the main port city three hours away by bus. I made an appointment for the next day and made a plan to get up early and call for a taxi from the hostel front desk. The next morning I woke up just before dawn, packing my laptop in my backpack. I padlocked the front door of my cottage, opened and closed the small front gate, and set off across the field to the Kamala hostel restaurant and office where the two donkeys (and probably my crocodile-fearing neighbor) watched me with wary eyes.

It was raining, which I had not anticipated, which in turn had caused the WiFi to go out during the night. I arrived at Kamala damp and sliding in the mud, offline, making my way up the low grassy hill which had turned into a muddy slope overnight. When I arrived at the restaurant, I found everything boarded up and the office closed. No one was there to call a taxi or reset the WiFi, and probably wouldn’t be for another few hours.

It’s important to note, while lovely and rustic, my cottage was not close to anything save a pair of donkeys and the empty beach. It was down a long dirt road, a 20 minute walk from the town of Montañita, and a 10-15 minute walk and river crossing to Manglaralto. I could walk to the main road, but that was another 15 minute walk perpendicular to the beach along a muddy dirt road. I had no WiFI, no means of calling a taxi, and it was raining and I had my laptop in my bag. My motorcycle didn’t have great tires for riding down slippery, muddy roads, and even if it did, there wasn’t a place in town I could safely leave it for an entire day. I weighed my options, and decided to walk down to the beach in hopes I could cross the river and walk to Manglaralto to the main road and catch the early bus to Guayaquil.

I arrived on the beach, and with the addition of the rain and the outgoing tide, the river was now roaring out to sea. A long rip current stretched out deep into the sea, the color of mud. It wasn’t worth the risk, even without my laptop. I contemplated walking back up past Kamala to the road, but since Manglaralto was so close, perhaps there was a quicker path through the scrubby bush that lined the river. I had often seen people appearing on this path making their way to the beach.

I set off up the muddy path, my feet siding in the mud. The path went for a little way into the scrubby bushes, then suddenly ended in an expanse of shrubs and muddy sand, close to where I had once spotted a diseased and emaciated possum. The river to my right, dense bushes to my left, I staggered on hoping at some point I would meet up with the road. As it dawned on me I had probably made an ill-advised decision entering what now seemed now like a grassy wasteland instead of taking my chances with the muddy but known stretch of road, I slipped and fell into the mud. For some time afterwards I flailed around in the shrubs, going one way and then the next, lost in a sea of brittle grass, pouring rain, and shrubbery somewhere between the overflowing river, the sea, the main road, and Kamala Backpackers. I finally emerged at the main road 25 minutes later, covered in twigs and dirt and completely soaked. I walked briskly down the main road in the rain which began to fall even faster, arriving at the La Libertad bus stop a few minutes later to hop on the bus and sit for three hours in the freezing air conditioning in the wet clothes, clutching my backpack with my laptop inside like a shipwreck survivor.

***

I arrived at the bus station in Guayaquil a little over three hours later, ran through the enormous terminal to the taxi line, took the taxi to the iShop, and waited covered in dried, flaking mud in the carpeted office where I explained the situation and was told I could come back tomorrow and pick up my laptop first thing. Not anticipating an overnight stay, and not wanting to go back to Montañita only to return the next morning, I spent the night in Guayaquil at a cheap hotel I liked called Atlantic Suites. Still in my muddy clothes, I used the tiny bar of cheap lavender soap to take a shower and clean the mud out of my clothes, and slept naked on top of the crunchy quilted blanket, dreaming of the sea.

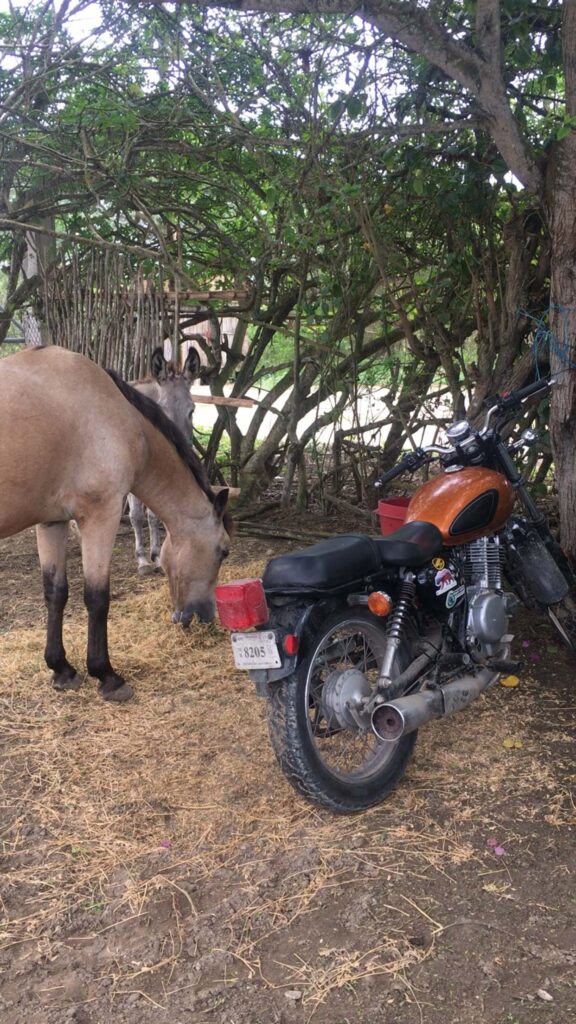

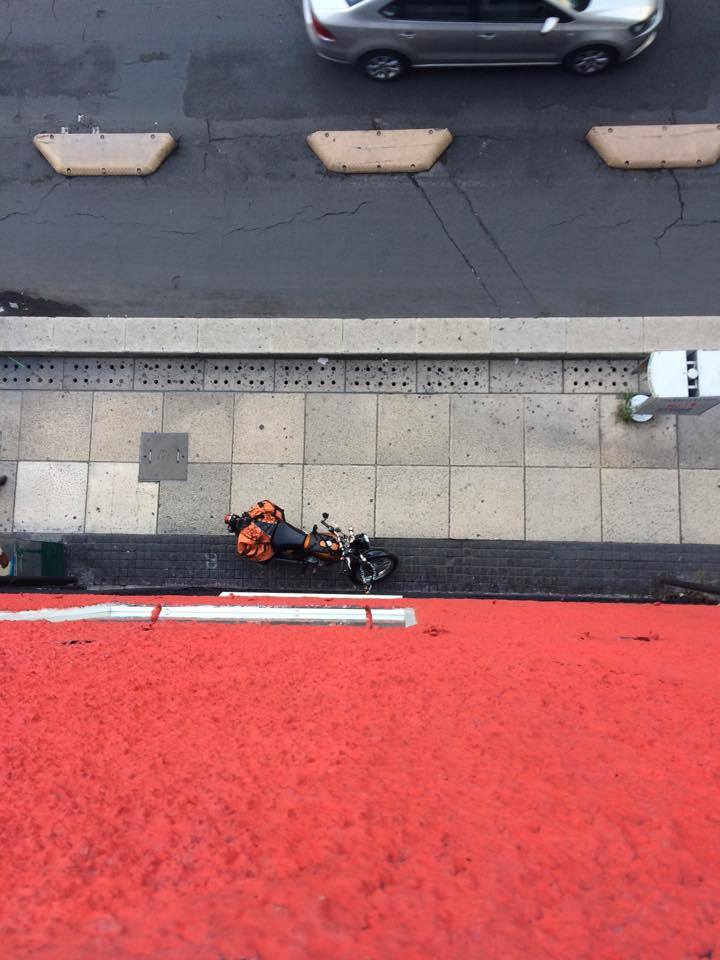

- The cottage and my motorcycle.

- The road to Kamala.

- The cottage.

- Needlefish on the beach in the morning.

- Sunsets from the beach.

- View from the lookout in the cottage.

- The Flores cart, many years ago.

- The remains of the shrimp laboratory.

- Lunches at the outdoor kitchen in the cottage.

- Sunsets.

- Pelicans flying over the cottage.

- The outdoor kitchen at the cottage at night.

- Pie de Limón on the lookout at the cottage.

- Reading.

- Montañita years ago when all the roads were dirt.

- Books.

- Tanya and breakfast alley.

- The donkey.

- Sunset from the lookout at the cottage.

- The parking spot.

- The outdoor shower.

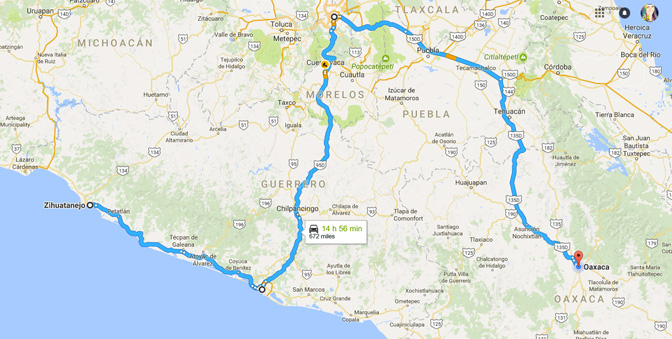

- Running route.

- The lookout at the cottage.

- Neighbors.

Alpha: Lael Wilcox on Pursuing Passion, and Encouraging Women to Get on Their Bikes.

For those of you unfamiliar with the sport of ultra-endurance bikepacking, Lael Wilcox is an ultra-endurance racer who in 2016 won the Trans Am Bike Race— the most notable bikepacking race in the world— and currently holds the women’s Tour Divide record. She was the first American to win the Trans Am and set the overall course record with her time on the Baja Divide route in 2015.

Sarah Webb of Long Rode Home and I were lucky enough to interview Lael as an intro to Alpha: A Lone Rucksack Series showcasing incredible humans in the adventure realm.

Before you became a household name in bike racing, you traveled around the world on two wheels with your then partner. What was your biggest take-away from that epic bicycle tour?

I definitely don’t feel like a household name in bike racing, but I’m really grateful that I get to do what I love. For me, no time on the bike is wasted. It’s time to think, to breathe fresh air, to ride somewhere real, sometimes to challenge yourself, sometimes to unwind. It’s all valuable mentally and physically.

I feel like traveling by bike is the best and most fun way to learn about different places. Riding through countries, I immediately get so interested in the place, people, terrain, seasons and how they relate to their neighboring countries and to other places I’ve traveled. I’ve gotten to make friends all over the world, many of whom I’m still in touch with.

One take-away is that it’s really a lot more fun and easier to ride through places in the right season, when the weather is good and dry. After a few wet, cold experiences riding predominantly into headwinds, I’ve started paying a bit more attention to weather and wind patterns– you definitely can’t control the weather, but you can choose to travel in good weather windows and just hope for the best. Probably the biggest take-away was that no matter where we rode, people were open-hearted and helpful. We were invited into so many homes and shown so much kindness.

What’s something someone once said to you to make you want to prove them wrong?

I started ultra-distance riding while working at a restaurant in my hometown, Anchorage, Alaska in 2014. On my days off, I’d ride as far as I could with very little planning or gear. I borrowed my mom’s road bike for these rides. On the first, I took the train from Anchorage to Seward and rode 127 miles back in a day. A couple of weeks later, my mom was flying to Fairbanks for a work conference. I flew out with her and rode the 375 miles back to Anchorage in 2 ½ days, riding directly to an 8 hour bartending shift (arriving twenty minutes late). I loved these rides. They felt so liberating. It wasn’t a race, the challenge was entirely solo.

Back at work, I was scheming up another ride. Talking to one of my regulars, I said I wanted to ride to Valdez, a 300 mile ride, and maybe take the ferry back. The regular’s friend scoffed at me and point blank said I couldn’t do it. I explained how I’d already ridden from Seward and Fairbanks and 224 miles to Homer in a day. He waved me away and said there were too many hills and I’d never make it. That made my blood boil and I just walked away. Two weeks later, there was a 400 mile road race, a qualifier for the Race Across America. The course traveled from Sheep Mountain Lodge to Valdez and back. I entered the race, not entirely sure I could finish it. I finished in 27 hours, the first woman and second overall (by 12 minutes). The regular from work sent me an email to tell me I was such a badass. I thought about his naysaying friend and smiled.

As you look back on everything you’ve done over the past 10 years, what advice would you give to a younger version of yourself?

I’d tell myself not to be so hard on myself and keep doing what I love every day. If you’re happy with your days, you’re doing the right thing. I also probably should’ve spent more time pursuing my own passions by myself.

Has a bird ever flown into you while cycling?

Oh man! I can’t even imagine how terrifying that would be. I’ve never had a bird flying into me. However, during a time trial on the Arizona Trail last spring, birds kept landing on the trail in my path at night. I think they were attracted to my light. I had to be really careful not to run them over. It was really eerie. Their eyes looked red in the night.

While a lot has changed for women in adventure sports in the past five years, what are the biggest challenges we still face?

I feel like I’m still facing discrimination. Some people are doubting my accomplishments. They’re not saying specifically it’s because I’m a woman, but they make excuses for why I have success. This past year on the Tour Divide, I faced online criticism for documenting my ride while there was another male racing with a film crew (that wasn’t criticized). Some men are too guarded to be openly sexist, but I feel like that’s the source of the negativity.

What’s the best moment you’ve had while on your bike?

I’m really big on riding through sunrises and sunsets while racing. Those moments are so special. Riding through storms, seeing animals, those are moments that I’ll never forget. I really love spending time on my bike, so it’s hard for me to pick a specific moment.

What are some of the worst attacks you’ve faced as a high-profile female racer and how have you dealt with it?

Dealing with online negativity concerning last summer’s Tour Divide was pretty tough and it still hasn’t gone away. I was intending to race the Atlas Mountain Race in Morocco this February, I’d gone as far as registering for the race, paying my entry fee, booking plane tickets and setting up a media project before running into problems with the race director. After successfully working together during the Silk Road Mountain Race, the race director decided that Rue would not be allowed to shoot me during the race because it wasn’t fair to other racers. Rue is a professional photojournalist and my girlfriend. She was planning on documenting the race for GCN. The Atlas Mountain Race is fully sponsored and there will be at least 2 other media crews on course focusing on specific racers. In the end, I think the race director is disguising his own financial gain and control with “fairness”. Out of 155 solo riders, only six of them are women. That’s 3.8% of the entire field. I’ve decided I won’t enter a race that doesn’t encourage women to participate and share their stories– there are so many other great races and rides.

We’ve noticed in several of your past interviews, questions asked by men making assumptions there is equality in sports for men and women, reflecting a lack of awareness at the additional obstacles women have to overcome just to get to the start of the race. What advice do you have for these men to become more aware of these issues? What questions would you like to be asked in the future?

I feel like I’ve had a pretty good experience with interviews. My main concern is for women just getting into the sport. For some reason, cycling is kind of exclusive and discouraging, maybe because it’s a gear heavy sport. I really want everyone to feel included. If we’re pedaling, we’re all doing the same thing– one version of riding isn’t better than another. They’re more the same than different.

Often we’ve been labeled as ‘badass’ or ‘not like other girls’ in our respective adventure tours, is there anything you’d like to say to women out there who have grown up with this sort of mentality, viewing women in the adventure sports realm as an anomaly rather than as part of the collective group of athletes?

At this point, this labeling seems generally positive, so I’m okay with it. If anything, I’d encourage people to be bold and pursue their dreams– you never know what’ll come out of it. You don’t have to be like everyone else to find happiness. I know riding ultra-distance isn’t normal and I’m not recommending that everyone get into it. However, I do feel like everyone can enjoy riding a bike on some level– it feels like being a kid again.

Top three book/podcast recommendations?

I love listening to audiobooks while riding. My recent favorites are the Robert Galbraith (pseudonym for J.K. Rowling) crime series, Lonesome Dove by Larry McMurtry and Eiger Dreams by Jon Krakauer. I’m always looking for new audiobooks. They help me stay up and alert through the nights while racing.

What’s your favorite dinosaur and why?

I don’t have one 🙂 I ran into a Gila Monster during my Arizona Trail time trial last spring and that seemed close enough. I love seeing animals on the trail.

Follow Lael on Instagram @laelwilcox

In Which I Drink My Own Urine

March 2018

The sun would rise at 5:33 every morning, but I rose before it, lacing up my shoes and pulling my hair back into a tie. I brushed a few pieces away from my face in one of the long mirrors in the boxing ring. A moment later I was off, feet pounding down the narrow walkway and out the gate, listening for the sound of motorbikes over the soft sound my shoes on the white hot concrete.

The air was so humid, seconds after I started running I was drenched in sweat. Over the next few hours the temperature would rise to over 90 degrees— getting up early was the only time cool enough to run outside. I was staying the month at Sor Vorapin Muay Thai gym in Bangkok, Thailand, training 6 hours every day: 3 hours in the morning, and 3 hours every afternoon. After every training session, my clothes were so soaked with sweat I’d wring them out in the bathroom sink before hanging them to dry in the clothes rack in my room— salty white streaks running down the backs of my black shirts and pants.

I had been in Thailand for two weeks now, and every morning was the same. Wake up early and see the giant orange sun touch the tops of the palms in the distance. Hobble down the wooden staircase. Lace up my shoes in the boxing gym, and go for a run. One, two, three, four laps. Walk back. Box.

I was still recovering from a motorcycle accident 7 months earlier which had broken both bones in my right leg at the knee joint, and torn the flesh open. That I was there at all was insane— I couldn’t jump, or do squats. My running was more of a hobble run where I consciously tried to normalize the gait of my right leg every step. I couldn’t jump rope, or do jumping jacks or burpees or move quickly, but I was there— and I was determined.

Sometimes there were five of us in the ring in the morning, sometimes two. We’d warm up with footwork on the large tire in the hot morning sun, jumping up and down in front of the large mirrors on its black edges, or running laps around the punching bags hanging in the middle of the gym.

There was an official warmup afterwards, then 5 rounds of sparring. Afterwards, a cool down which consisted of five different types of laps around the gym— high knees, legs up, alternating left and right hooks, modified jumping jacks while running, and burpees.

“Mostly it is loss which teaches us about the worth of things.”

―Arthur Schopenhauer

At first I didn’t realize the dog had a bird in its jaws. We had just finished up afternoon training, and I was sitting outside on a long brown bench icing my extended right leg, watching a sparring session in the ring. The pigeons had been flying over the gym all day, sometimes dipping low into the boxing area, sometimes flying so high I could barely make out their shapes against the sky. The dog was grappling with something to my right, growling and shaking its head from side to side. I didn’t realize what I was seeing— I didn’t understand the grey and white and red was another animal, and the dog was killing it.

After a few stunned moments— a bag of ice on my right knee— I leapt up and hobbled over to the dog, grabbing it by the back of the collar and wrapped my fingers around its open snout. The bird fluttered away to a nearby corner.

Other students gathered around as I slowly crept over to the injured bird. Its right wing was bent, and it looked reproachfully at the crowd in front of it. The gym was always loud, music pulsating in the background, people talking and hitting and wrapping their hands— but in that moment, the small area outside the boxing ring became absolutely still. It was as if my vision had greyed around the edges and there was only me, and the pigeon. Despite the pain in my right leg, I slowly crouch-walked over the where the bird stood on a small ledge.

My skin glowed in the evening light, sweat slowly running down my legs. It felt like everything that had happened over the past 7 months came together in a moment— the accident, the hospital, the wheelchair, feeling alone and crippled— this bird was also hurt. Its right wing was injured, and to me this felt like a sign. If I could help this bird, everything was going to be okay. I knew this bird had been sent to me like some sort of cosmic test, like the witch disguised as an old woman in fairy tales begging for bread on the street, and if I didn’t help this bird, I would never heal— my leg, my heart… my spirit.

I knew it was nonsensical, but in that moment, as I crept toward the bird, the deepest most desperate desires at the bottom of my heart came to life. I felt connected to the moment when I was on the side of the road after my accident. I was no longer a person softly approaching a small bird— I was approaching myself, lying there in the hot sun. I was lying there, waiting, waiting for what came next. Wondering what could come next. Hoping it would be met with kindness.

I reached out, and carefully wrapped my hands around the bird. It didn’t move, it only watched me with its round orange eyes, surrendering herself to her fate.

“It’s going to be okay,” I whispered.

“Love doesn’t just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread; remade all the time, made new.”

― Ursula K. Le Guin

That night after training, every muscle in me ached. When I inhaled, I could feel every rib on either side of my chest aching all the way down my sides. I rolled over onto my stomach, groaning, leaving my right leg to dangle off the edge of my bed, slowly letting the weight of my foot straighten my leg. I desperately had to pee. It was a side effect of all the sweating in the intense heat— drinking gallons of water a day. I was constantly filling up my Nalgene from the water cooler. A boxing session for 7 minutes, an entire Nalgene of water. Dry off, repeat.

The thought of climbing out of my tiny bed, walking the length of the long hallway to the rickety staircase, down the stairs, across the boxing ring, and into the corridor where the bathrooms were, was almost unbearable to think about.

The staircase was my nemesis. I hobbled up and down it several times a day, mostly using my arms and my one good leg. I couldn’t do it. I eyed the two large, empty plastic water bottles sitting in the corner of the room. I had been meaning to take them downstairs to recycle. I slowly pulled myself up from the bed moaning, and hobbled over to the tiny fridge in the corner where my duffel sat perched on a small stand. Digging around in the bag, I finally found the small, silver nail scissors and sat on the floor with both legs extended in front of me. I slowly cut the tops off the two water bottles, one small snip at a time, their flimsy plastic giving way to the tiny scissors.

I peed in both the bottles under the bright, halogen light of my small room above the boxing ring, the frigid air of the AC unit blowing across the tops of my exposed legs. I filled one enormous water bottle then another, switching out the bottles like a champ, like I peed in bottles inside all the time for sport. There’s nothing— nothing— more freeing than peeing into a bottle in the middle of an open room, soft cool air caressing your thighs. I felt feral. I may have been contained in that room, unable to descend the staircase, unable to walk properly or squat or step down off a curb without wincing— but could pee wherever and whenever I wanted.

I carefully— carefully— placed both full plastic bottles next to one another in the corner under the AC unit. I gleefully hobbled back to bed and fell instantly asleep.

***

The pigeon barely struggled in my hands, my fingers wrapped around it’s tiny soft body. I could feel the shape of its wings under my fingers, the smoothness of its feathers. I softly whispered to it, over and over and over.

“It’s fine, it’s fine, it’s fine.”

I didn’t know what to do. I knew the pigeon was hurt, but I wasn’t sure to what extent. My hope was that if I found somewhere safe outside the compound, away from the dogs, she would be able to fly away on her own. So I walked. I walked down the tiny concrete road in Bangkok, no wider than a sidewalk, like a long bridge— the waterways lining the streets three feet below. The tall, lush palms surrounded us on either side in the evening light, and every so often I’d stand as close to the edge as possible while a motorbike roared past.

As the road made a turn, a small section of pines lined the edge of the street. It was here the pigeon started to struggle. “Just a little longer,” I whispered, wanting to take her to the open field at the edge of the road where kids would play soccer during the day.

She struggled out of my grasp and in a moment, had wriggled inside a small gap in the pine trees, and was now barricaded by dense, prickly branches. We stared at each other for a few moments, then I went back to my room and cried.

“Words have power.”

― Mira Grant

When I woke in the morning, I had almost forgotten about the bottles of urine I had stashed in the corner of the room. I could barely get myself downstairs, how was I going to balance two full bottles of urine down the rickety staircase, across the boxing ring, and into the toilets unnoticed? I looked around the room for a solution. Sometimes the manager of the boxing gym would come into the rooms during the day, and the last thing I wanted to explain was why I had two mutilated plastic bottles in my room full of urine.

My empty Nalgene water bottle lay on my bed. I thought carefully for a fraction of a second, then, carefully, slowly, poured the contents of the water bottles into my empty Nalgene. The bottles were ice cold from having spent the night under the AC unit. Thinking of what anyone would say if they walked in and saw me pouring my own urine into my Nalgene, I let out a loud cackle.

I screwed the top back onto my Nalgene, now dewy with cold, and slowly crept out of my room and down the long hallway to the stairs. Holding my Nalgene in one hand, I lowered myself down each step as quietly as possible, as if I were removing a dead body instead of a bottle of pee. I reached the boxing ring without encountering a soul. I set my Nalgene down on the end of a bench, and ran to the bathroom corridor to make sure it was empty. There was no one. While I’m here, I thought, I’ll quickly use the bathroom, wash my hands, then go back and empty the water bottle into the toilet.

Two minutes later, I walked out of the bathroom corridor, the sun’s rays already streaming into the gym. The heat was overwhelming. I walked to the bench to grab my Nalgene to take a swig of ice cold water before I headed out for a run. I stared into the distance thinking about training that day as I unscrewed the cap of my Nalgene, and took a swig.

It wasn’t water. I ran to the bathroom.

***

I stopped by the section of pine trees, clutching a small bag of potato chips in my hands, peering low under the branches. There she was, the white of her feathers glowing slightly in the gloom. I opened the bag of potato chips, broke them into tiny pieces with my hands, and reached as far as I could into the dense branches to leave a small pile in the clearing. She immediately started pecking at the crumbs.

I crouched at the edge of the trees for awhile, watching her eat.

“I’ll be back soon,” I promised.

***

Less disgusted with myself than I should have been, and giggling madly, I scrubbed the inside of my mouth with soap. The water couldn’t have been any hotter, I winced as I held my Nalgene under the tap, filling it and scrubbing it, again and again and again, until it was clean.

“Upper. Cross. Jab.”

I hit as hard as I could every time, my legs and fists and elbows striking the pads. I’d think about all the muscles and tendons in my leg, and my patella, and how it felt to feel the pads on my shins, the sound of my skin on the thin, black plastic. I thought about the thin protective padding around my fists— how delicate they were really, my boxing gloves. I felt the slow drip of sweat off the tip of my nose.

“Finished.”

***

Later that day, I stopped by the pine trees again. The pigeon was gone.

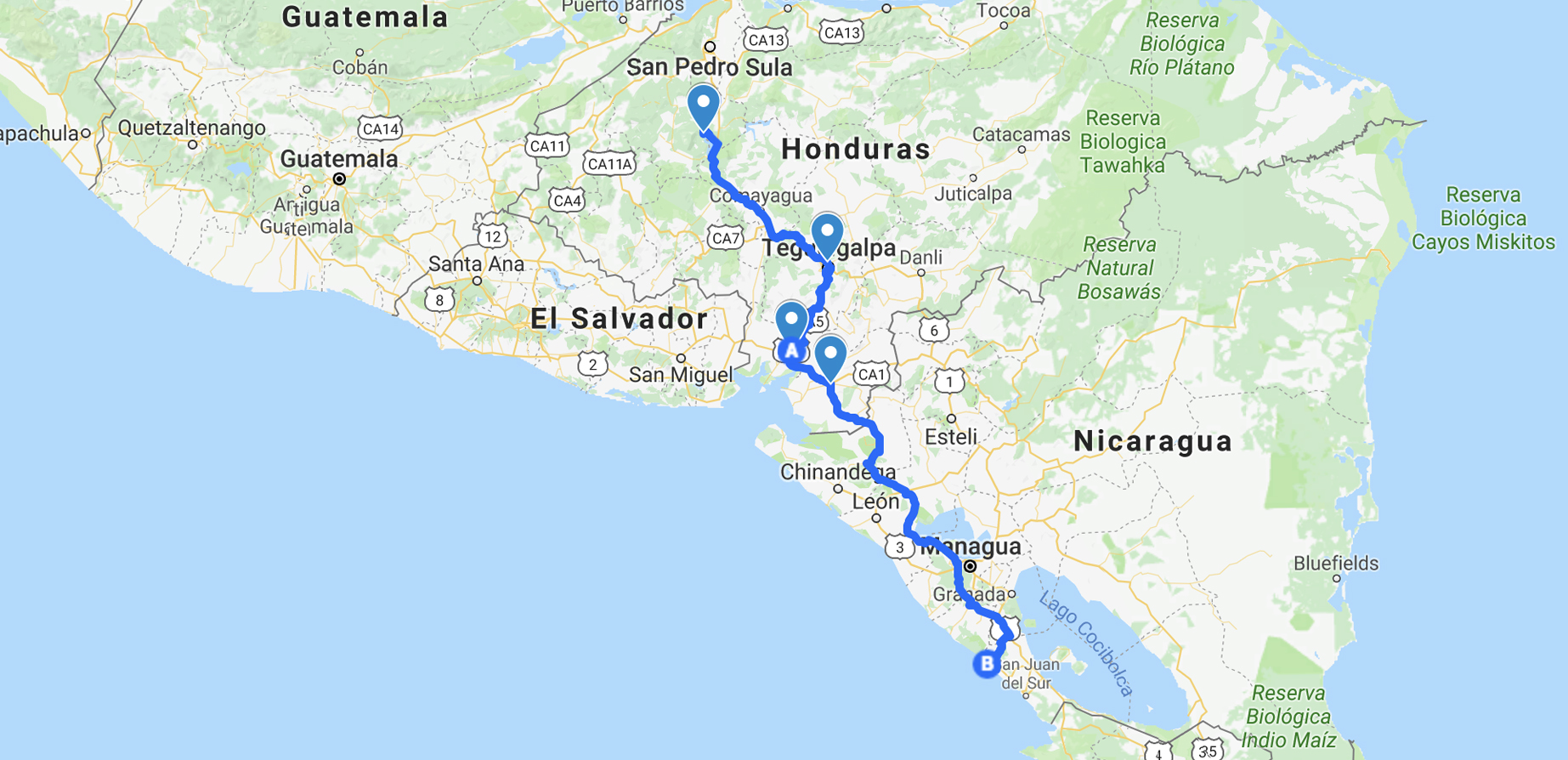

Heading South: The Return of #FindingFitzRoy

Honduras

The sun is brilliant rising, warm oranges reaching from behind the mountains, touching the leaves on the trees and slowly making its way across the road. The pale shapes of the morning take form and become the highway, and I am no longer a shadowy thought but real, and present, and riding again, illuminated by the sun.

The empty road stretches into the green ahead, the mountains in the distance to my left. The cool wind blows over my shoulders and into the collar of my riding jacket, and every few minutes I glance behind to see the pink, golden rays of the sun.

***

Only the day before I had started riding again, loading up my bike in San Pedro Sula, the same straps and bags and gear, like I hadn’t been gone from this place an entire year, like the accident hadn’t happened. But it had. Eleven months earlier I had been hit outside this very town when a truck crossed the highway in front of me. He clipped my motorcycle and threw me across the road, breaking both bones in my right leg, tearing my leg open from left to right. Months after the accident I had vivid dreams where I’d wake up sweating, reliving riding down that same stretch of highway, the slow motion of the truck, the swerve, lying in the dust on the side of the road. The way it felt to lie alone in a dark corridor in the hospital bleeding, how it felt to sit in a wheelchair day after day, staring out the window. How hard it was to put one foot in front of the other and keep moving. After almost three months in a wheelchair, one month on crutches, and seven grueling months of physical therapy and gym sessions and recovery, I had flown back to San Pedro Sula to fix my motorcycle and continue my trip, heading south to Fitz Roy.

For the past three weeks in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, I had taken my bike from one place to the next— the machine shop to re-drill the oil filter cap that had been sheared off in the accident, the paint shop to repaint the fenders, and almost every government customs office in and around the city to sort out my overstayed temporary vehicle import permit.

At night I stayed at a tiny hostel in the hills of San Pedro Sula, and in the mornings Anthony— the grandfather of the Villanueva family who had stored my bike and used his connections to get me into surgery the year before— picked me up at my hostel and we’d drive around the city, slowly piecing together my bike. We’d stop by his home in the afternoon, where his wife Rafaela would be waiting with lunch. The second week, I thought I’d have to take the bus to Guatemala City to pick up a part that wasn’t available in Honduras. The third week, we discovered the fuel pump was bad.

I couldn’t clarify the mix of emotions pumping through my extremities. If I kept moving fast enough, I didn’t have to think about how I would feel when the bike was done, or what it would be like to start the engine and ride off down the road. I didn’t have to think about how it felt to roll across the highway and come to rest in the dirt. If I made lists of parts and costs and timeframes, of phone numbers and spanish translations, I could think about everything else later.

***

After three weeks, what seemed like forever and too soon all at once, my bike was ready. One afternoon, Antonio dropped me off at the Suzuki dealer, my motorcycle bags gathered in my arms. I threw a leg over the bike, and settled onto the seat. It was a pale grey day, the unremarkable kind that settles into the background. It was so hot my tank was soaked underneath my motorcycle jacket. I rested my hands on the handlebars, trying to make sense again of the way it felt, like coming back to a place years later I barely recognized. Key, safety switch, ignition. There was a loud buzzing in my head, so loud it seemed to drown out all the things I used to know and think about getting on the bike, it was louder than my own thoughts and made me fumble awkwardly every step.

My heart felt higher in my body than it ever had been as I slowly released the clutch and rode toward the busy intersection. I didn’t want to. Riding onto that busy street, I realized, was the last thing I wanted. Every part of me screamed not to, that it was wrong and dangerous and too loud, everywhere. The buzzing in my head and the sound of the cars, I could hear the thunk they made riding over the uneven surface, feeling every bump in my arms, every noise the sound of a rider being struck and scraped and thrown. I could feel the scar stretching around my right leg so much my leg started to hurt, and I noticed how frail and exposed it looked there, resting on the outside of my bike.

“It’s okay it’s okay it’s okay,” I whispered to myself over and over and over, as I released the clutch and accelerated into traffic. “It’s okay it’s okay it’s okay,” as I rode past an intersection where a giant truck had just t-boned a car. The carcass of the vehicle, now bent in half, rested on the curb. “It’s okay it’s okay it’s okay,” as I headed up into the hills. I stopped hearing the words I was saying— I could have been saying anything at the moment, it was the mantra I needed, the repetition of something to hold onto and focus.

I pulled into the drive at my hostel, turned off the engine, and crouched next to my bike, shaking. I wanted something, some sort of commemoration or swelling of music, some deep conversation that would end in character development and a new perspective— but it was just me. It was just me in the hot sunshine, standing next to the motorcycle I had spent weeks repairing, and the body that had spent eleven months working every day for this one.

***

Five years earlier I had learned to lead climb— the type of climbing with no attached rope at the top of the climb, but a series of carabiners leading up to the top where the climber would attach the rope as she climbed. When falling, she’d drop as far as the last place clipped in, further still depending on how much slack there was in the rope from the belayer.

One day, I was climbing with an friend to improve my lead climbing skills. “You need to practice falling,” he told me, “it’s the only way to not be afraid of the climb, to keep going.”

I climbed to the top of the wall, ending the route holding onto a large hold. “Let go,” he shouted.

And even though I didn’t want to, even though it felt wrong and dangerous and stupid, I let go of the hold, and leaned back into nothing. I fell fifteen feet before he caught me, my whole body lifting into the air as the rope caught. When my feet touched the mat again my legs were shaking, and even though there was nothing funny, I laughed. Years later I think about that moment— not what it felt like to fall but how it felt to start climbing again afterwards, knowing the drop was always there, waiting.

***

Honduras

Days before I left San Pedro Sula, an enormous eruption in Guatemala to the North-West left sixty-nine dead and hundreds injured, and simultaneously violence erupted in the neighboring country of Nicaragua to the South-East. It felt like Central America was imploding, and I was sandwiched in the middle with my motorcycle. The US Embassy in the capital city of Nicaragua was closed due to the unrest. The violent protests against the president, Daniel Ortega, had reached a peak, and it was rumored the border between Honduras and Nicaragua had been closed as well. Almost one hundred people had already been killed, and every day I watched the news as more violence erupted and scenes of people lying dead or being carried bloody in the arms of fellow protestors filled the news— first in Managua, then Masaya, then Granada. People ran through smoke filled streets wear masks and waving Nicaraguan flags and holding signs, while military police shot into crowds. Only the day before a man had been shot and killed trying to flee down the street on his motorcycle.

In just a few short weeks, what had started as a protest against Daniel Ortega for slashing social security and pensions had escalated into a potential civil war. Young people around the country erected roadblocks on all major thoroughfares to stop commerce, and it was rumored were willing to use violence on anyone who tried to pass. Small towns affected by the road blocks were running out of water and food and gas. Protests began erupting in farther flung places— Esteli in the North and Leon to the Northwest— right where I’d be riding through. For days I checked multiple sites, tracking the violence and planning the best route to cross the country. The day before I left, I wasn’t even sure I’d be able to cross the border. Since the popular bus line Ticabus was still running routes into Nicaragua from Honduras, I decided to go. I’d leave as early as possible at first light to cross the border into Nicaragua and ride through as much of the country as possible before dark.

***

Honduras

I woke half an hour before sunrise to load up my bike, outside the window everything one continuous shade of purple-grey. The sun had only just begun filtering through when I arrived at the Nicaraguan border. Inside, a woman heavily stamped my passport. “You know what’s going on right now don’t you?”

“I know,” I said, “I’m going to cross the country as quickly as possible.”

“Good luck, and be careful,” she said, sliding my passport back across the counter.

The roads quickly changed from disrepair to beautiful, flat stretches of black. It was exhilarating to accelerate on and on and on, without the heavy traffic and danger of debris and potholes. Riding in Honduras had been like an endless game of frogger, but Nicaragua was a fresh cool breeze, it was easy. The smooth empty highway snaked through the flat, green countryside in the sunshine, a tall volcano in the distance, smoke curling overhead. An hour after crossing the border I ran into my first roadblock. All of sudden, there was a line of trucks in my lane, stretching all the way into the distance. There were no brake lights, or smoke, or sounds of engines running— just a long, quiet line stretching on and on and on. It felt like a scene from an apocalyptic movie, where everything was too quiet, not another human in sight.

I accelerated into the left lane, passing one truck, then twenty. I could see something in the distance stretching across the road, what looked like a white wall. I caught up to another motorcyclist in front of me, and cautiously followed behind. We both slowed, and I realized what had looked like a wall was actually sandbags stacked high across the road, with a narrow passage in front of the left lane barely wider than a motorbike. A pile of packed sand lay in the pathway, and people in masks holding sticks and metal bars strode around the other side of the wall. A tuk tuk was trying to squeeze through the opening, its tires spinning in the sand, the other motorcyclist and I waiting behind it.

As soon as the tuk tuk was through, the other bike accelerated behind, maneuvering through the pile of sand and across to the other side. No one seemed to take any notice of me, and I held my breath as I quickly darted through behind the other motorcyclist, and accelerated into the right lane.

I rode for another two hours, crossing through the capital city of Managua without seeing roadblocks or violence. An hour outside the capital the road rose into the hills, and I started following another motorcyclist around the tight turns, the sky turning dark overhead. The air turned chilly, and a fog rolled in as we rounded a tight turn and the road ended in chaos.

Tractor trailers looked as if they had been thrown across the road, touching buildings on either side where people on foot squeezed through. Cars were abandoned in front of the trucks, forming haphazard, narrow walkways in between where people milled around. The smell of smoke was in the air, and a kind of electricity— like something was about to erupt.

There was no going back, and it looked like there was no going forward. I sat on my bike, watching the scene unfold.

“All of a sudden there was a shout, and the motorbikes around me erupted to life. The crowd of bikes surged forward toward the narrow opening in the sandbags.”

The motorcyclist in front of me rode up onto the steep curb where the sidewalk ended, and along the path I had seen people squeezing through from the other side. Up close, I could see a narrow footpath along the grass, the truck to the right, and to the left a steep drop down the hillside. He quickly maneuvered the bike around the sharp corner and disappeared. I sat there quietly for a split second. There was no turning back. I took a deep breath, and riding the clutch, leaned to the left and accelerated, hoping my pannier bags would clear the truck and not topple me down the embankment to my left. The bike bumped up and down, and I turned the front wheel to the right and leaned hard to the left as far as I could go without losing my balance and falling to the valley far below. A little more power. The rear wheel spun on the grass, and with a quick blip to the throttle I was back on the narrow path above the road.

I followed the motorcyclist for thirty minutes through the maze of trucks— it was the hardest riding I’ve ever done. He didn’t look back once, but always seemed to wait after each obstacle, then continue when I appeared behind him. My shoulders ached with keeping the bike upright, my stomach burning from leaning left then right, carrying the weight of the bike on my legs and arms. I rode down slippery grassy pathways, up steep curbs, down sidewalks scraping my turn signals on the tight passageways when there was barely enough room for a person to squeeze through, between the trucks and the buildings. I rode up a narrow slice of slippery tile the length of a truck, hardly daring to breathe as I balanced my bike on the sharp edge. Finally, after squeezing between an abandoned storefront and a truck to my left, there was the last section of the roadblock in front of us— a low wall of white sandbags. Motorcycles were parked everywhere, and groups of people in masks shouted and ran the length of the sandbag wall, higher than the last one. The smell of something recently burnt hung in the air, and smoldering ashes lay on the pathway through the roadblock.

“This is the moment where something serious happens,” I thought to myself, as if this weren’t serious enough. I inched forward toward the passageway, pulsing the throttle, every inch of me alert. I had no idea what to expect— I was obviously a gringa, in my all black riding gear and bright orange motorcycle with a foreign plate, my blonde hair in a braid slung over one shoulder.

There was so much life, and shouting, flags waving overhead and people perched on the beds of trucks. I was surrounded by motorcycles, motorcycles parked along the edges in front of semis, motorcycle squeezing into the spaces around I hadn’t noticed until our elbows were almost touching. All of a sudden there was a shout, and the motorbikes around me erupted to life. The crowd of bikes surged forward toward the narrow opening in the sandbags. Suddenly, a man sitting on a platform next to the wall shouted, “Gringa! Gringa!” pointing at me.

A group of men sitting on a truck platform turned to me with shouts, “Hermosa! Guapa!” The man at the front threw his arms wide with a huge smile and started blowing me kisses and waving wildly. Heart pounding, I inched through the narrow sandbag passage over piles of ashes to the chorus of ‘beautiful!’ and blown kisses.

View this post on Instagram

***

One Year Earlier, San Pedro Sula

I lay in an empty metal van, bouncing up and down over speed bumps that lined the road, potholes jostling my body, blood running down my leg underneath a dirty dish towel covering the open bone. My back was raw and bleeding from being scraped across the asphalt, small pebbles coating the raw, bleeding skin.

A woman was in the van with me. She had climbed in the bed of the truck at the accident, and again when I was transferred to the van— two men sliding me into the back on a simple, canvas stretcher. She was carrying the bags from my motorcycle and my helmet, and had stuffed my passport down her shirt to keep it safe. “You never know who to trust,” she told me, as she held my hand. She held my hand when they unloaded me at the public hospital, and again when they were setting the bone while young interns bustled around me. I was shaking— the room didn’t seem real, like I was watching a slow motion film that shook at the edges, but I could feel the weight of her fingers around mine.

I found out later she was a passenger in the truck that hit me— her brother had been driving. The whole time, she knew. She knew her brother was responsible, she must have felt the weight of my motorcycle hit the truck, seen me thrown across the highway.

Whatever her motives, she didn’t have to be there, watching over my bags and keeping my passport safe, talking with the doctors and offering to help in any way she could. In all the eleven months I spent recovering, it was this woman— a stranger who in a distant way held some responsibility for the accident— who held my hand.

***

Nicaragua

The road was on fire. Uneasily, the other motorcyclist and I glanced at each other. Smoke billowed 100 feet away where a giant truck was jackknifed across the road, a crowd of people shouting and circling it as great flames rose up to touch the smoke above. We’d been riding together for a few hours, and now, we were trapped between the enormous roadblocks and the flames ahead. We sat there in silence, unsure how to proceed, stopped in the middle of the lane some distance away from the flames.

Slowly, cautiously, we both rode forward. When we got closer, we saw it wasn’t the truck that was on fire but giant palm fronds aflame in the road. A pile of glowing red embers lay scattered around the dying fronds in front of a group of people in masks. Through the smoke, we could see cars waiting on the other side, unknowing the road was completely blocked in the other direction.

After a few minutes, the people in masks cleared the palm fronds, and gave a signal for us to ride thorough. Smoke surrounding us, I held my breath as the flames licked the ground to my right. The smoke burned my eyes, and I slowed to ride behind the glow of the taillight of my fellow rider, passing the long snake of cars to the left.

“In the violence erupting around us, those small acts of human kindness are what I remember most. Moments that on their own were tiny and delicate, but filled my heart with the brightest golden light.”

There was no gas. Gas stations were roped off with caution tape, people were everywhere in the streets. I rode through small towns where military police watched the road blocks from a distance, arms folded. I rode past lines of cars stretching miles and miles, motorcycles riding directly at me in the opposite direction, the only way through the roadblocks.

It seemed there was always someone riding with me, even after my fellow motorcyclist and I parted ways. For a time, it was a man and a small boy, then a group of motorcyclists riding down the same deserted stretch of highway. I stopped at one point to adjust my tank bag, and a motorcyclist I had been riding with for some time circled around to wait for me, and then we continued. Without saying a word, we were all riding south together, and would wait for each other to move on. In the corruption and violence erupting around us, those small acts of human kindness are what I remember most. Moments that on their own were tiny and delicate, but filled my heart with the brightest golden light.

***

I arrived in Popoyo 11 hours after I started riding from Honduras early that morning. The last two hours were down a muddy, dirt road in which I made two river crossings, unloading my motorcycle and slopping through knee high water carrying my bags across before returning to ride my bike through.

I arrived to the most brilliant white sand beach and perfect, arcing blue waves, soaked and exhausted and covered in mud. I stayed for one week on that coastline, listening to the news and talking with locals about the government and violence and dwindling supplies in the small towns on the coast. At the end of the week, I bought gas from couple on the side of the road just outside of town, chickens flocking around my bike. The man filled my gas tank from an old 2-Liter Coke bottle filled with gasoline. It didn’t quite fill the tank, but would get me across the border to Costa Rica where there would be gas.

Nicaragua

I rode out of Popoyo at 5 AM on a Saturday, my body leaner and stronger than it had been the week before, the dirt road completely empty, the ocean waves crashing on one side and the sound sitting quietly on the other.

It wasn’t without cost, this freedom to ride a motorcycle down a remote road in Central America at dawn, to watch the sun rise and feel the wind. How easily it could be taken away, but how appreciative I was of it then, how delicate and fierce life could be at the same time. I rode on, up hills and through valleys, winding along to distant places, leaving behind the woman I had been last year, before the accident. I could remember her, if I tried, like trying to see a room by candlelight— glimpses through the darkness. The longer I rode the less real she became, until there was only one of us, and I rode on.

Read more about #FindingFitzRoy here.

In Which I am Hit by a Truck

On the Road from La Ceiba to Tegucigalpa, Honduras // 10 AM

The rain that had filled the potholes on the red dirt road had gone, leaving only empty spaces. My motorcycle bumped up and down as I leaned right and then left, slowing down then speeding up, navigating the twisting road that followed the river through the jungle in Honduras.

I had spent the last two days at a small lodge overlooking a river just outside La Ceiba, giant stones hanging over small rapids that ran through a narrow channel of stone, mist rising from the jungle on the opposite shore. The northern secondary road I had planned to take all the way to Nicaragua from La Ceiba was really just a pot-holed dirt road, so I had decided to take the main highway all the way back to the capital, and head to Nicaragua the following day.

I pulled up to the main highway, leaving the jungle behind me. The roar of the traffic filled my helmet—dusty motorcycles tearing down the street, dilapidated pickup trucks without mufflers and roaring buses spewing dark smoke. Trucks rounded sharp bends while playing chicken with the oncoming traffic, barely missing motorcyclists who would dart in between cars to avoid the passing trucks. Bicyclists rode across streets seemingly unaware of oncoming traffic, pedestrians crossed highways with small children and strollers. Near speed bumps, taxis squeezed by 18-wheelers on the shoulder attempting to move ahead in the line of traffic. It’s like the Wild West, I thought to myself.

At a traffic light in San Pedro Sula, a group of eight small boys ran in front of my motorcycle, then ran back to the sidewalk, than ran out again in the span of ten seconds. I breathed a sigh of relief when I exited the busy city. It’s dangerous to ride a motorcycle anywhere, but in Honduras, I discovered a sort of lawlessness I’d never seen before.

Only a few days earlier, I’d seen a motorcyclist wreck on the same highway. The two lane road stretched up the mountain, and where there was only road, suddenly there was a twisted carcass, like an animal that had tried to cross and was hit. Even then, it seemed like a warning. A crowd of people on the side of the road carried the rider’s body away— a piece of the strewn machine. For the next few days, I remembered the shape of the motorcycle lying across the road, parts of the bike strung across the highway like entrails. Even though I knew it was a bike, I remembered it as an animal.

***

The two lane highway wound through small hills and gas stations, the side of the road dry and dusty. A banged up red truck was in front of me, long metal beams sticking far out from the bed of the truck. There was no one in the distance in the opposite lane, the road stretching on into the horizon. I moved into the left lane, accelerating around the truck.

All of a sudden, a green pickup truck darted in front of the truck I was passing from an opposite street perpendicular to the highway, driving across the road and stopping in the lane directly in front of me. I only had a fraction of a second before I hit, and swerved toward the tiny space left of the road in front of the truck, even though I knew I couldn’t possibly fit. I was riding at 60 mph, and I distinctly remember that tiny bit of negative space, and knowing I would hit. It was only a split second, but it seemed longer—my mind perfectly clear, the road stretching into the distance, the bright sun shining on the shoulders of my motorcycle jacket— and that small, open shape I aimed for.

All of a sudden, I was rolling. I rolled and rolled— I spun across the asphalt, seeing nothing. I could feel the yellow heat, the sound of the gravel underneath my body, and, the metal screech of the motorcycle as it slid across the road— hoping, even as I uncontrollably rolled, I wouldn’t be hit by it. I could feel the weight of the sound, the sharp high-pitched scream of something devastatingly heavy, like an anvil shot across the pavement, something only seconds before had been my ally turned into a 350 pound steel projectile that could easily kill me.

The first thing I saw through my visor as I opened my eyes was a clump of grass my helmet came to rest against. I immediately struggled to pull my helmet off, but couldn’t. At once I was surrounded by people in the bright light, hands behind my head helping me pull my helmet off. Hands started to pick me up. “Don’t move me, don’t move me,” I said in English. If I had a head or spinal injury, I didn’t want to be moved in case it caused further damage, which in itself was a ridiculous thought as I was on the side of the road in rural Honduras, and realistically no one would be arriving with extensive medical knowledge to safely move me to a hospital, spinal injury or not.

I lay on my back, the high-top boot on my right foot halfway on and halfway off, severely spraining my ankle. Something was wrong, but my body seemed disconnected from my brain— I felt nothing but extreme discomfort. I slowly opened and closed my hands. It didn’t feel like I had a head or spinal injury. I could feel hands unlacing the boot and taking it off. As I struggled to pull myself up to my elbows, thinking in a few moments the pain would subside and I could stand, that I would be fine, I saw the pile of open, torn flesh where my knee should have been. “Don’t look don’t look,” a man tried to push me down. “It’s fine,” I said, waving him off.

The skin around the knee is thicker than I thought it would be, I thought, as I examined the sliced open flesh, the lengthwise open piece of skin. Blood trickled out the side of the wound extending from one side of my leg to the other. A bone protruded from the open flesh, so foreign at the time, so utterly out of place when I looked at my leg, I didn’t realize it was my exposed patella.

“Nobody can hurt me without my permission.”

―Mahatma Gandhi

San Pedro Sula, Public Hospital // 2 PM

Hands grabbed at my torn jeans, scissors cutting through the torn fabric from bottom to top, snipping through pockets and belt loops, the metal edge of the blade cool against my skin.

“I didn’t like those jeans anyway,” I said groggily to one of the younger interns in Spanish.

I had arrived at the public hospital in San Pedro Sula after riding in the back of a police pickup truck, my right leg extended out in front of me, a dirty dishtowel draped over my torn leg. Someone in the crowd had called an ambulance, but after lying on the side of the road for fifteen minutes I asked a group of men to pick me up and put me in the back of the police pickup. I asked a woman in the crowd to bring my orange tank bag and red backpack, and the keys to my motorcycle— I didn’t care about anything else, those bags held all my paperwork and camera equipment. Hands underneath my arms and legs deposited me into the bed of the truck like I weighed nothing at all. I didn’t even look for my motorcycle, my world shrank in those few seconds the driver of the pickup decided to cross the highway without looking.

Ten minutes down the road, the police truck stopped. “There’s the ambulance, do you see it?” pointed the woman next to me in the pickup. I expected to see the equivalent of what I was used to in the United States, but what appeared was a stripped metal van. Two men brought a stretcher, slid it into the bed of the truck, and I rolled myself onto it, supporting my injured leg. They deposited the stretcher onto the floor of the empty van, where I bounced up and down on the roads to a private clinic. The medic, the first responder I had seen since the accident, chatted with me a bit, but clearly had no first aid experience. Twenty minutes later we arrived at a private clinic, where they wrapped my leg loosely in gauze, then put me on another stretcher and into another ambulance to transfer to the public hospital.

I lay on the cold table in my underwear, a papery green gown draped overtop my upper body. Two male doctors walked into the already crowded room, standing at the end of the table. One of them held my x-ray and poked at my leg with two fingers, making me gasp in pain. “Fracture,” one told the other. Ignoring me, they both walked out of the room.

“We need to clean the wound,” one of the interns told me, “It’s going to hurt.”

Minutes before, in the waiting room, a young man standing there came up to my bed as I waited, lying in the stretcher. “I love the American people,” he said. “I hope this terrible thing does not give you a bad impression of our country.” When they wheeled me into the examination room, he walked in with me. As they started to clean the wound, this young Honduran man I didn’t know held out his hand, and I took it. I lay staring at the ceiling tiles, squeezing and squeezing his hand as the two interns set the fracture, and cleaned the open laceration on my knee without anesthetic. “I hope you won’t judge our country by what this man did to you,” he said. I never saw him again.

“She is of the strangest beauty and the darkest courage, and when she walks with intent the earth trembles beneath her feet.”

―Nicole Lyons

San Pedro Sula, Public Hospital // Friday, 6 PM

My whole body shook underneath the paper gown, my teeth chattering and my right leg almost completely numb. I knew I was in shock, and I had lost a lot of blood, but there were no blankets or doctors in the dimly lit hallway where I was lying on a metal stretcher. My bed was against the wall at the end of a line of beds full of Honduran men who had also been in motorcycle accidents— most of them draped in swathes of white cotton gauze, white extremities in plastic beds.

I was waiting in the hallway to go into surgery with the orthopedic surgeon, to clean and close the gaping wound in my knee which was packed with dirt and gravel. “You need to get back to the states,” one of the nurses told me. “We don’t have the equipment to fix this here, you need to go to a better hospital,” he said anxiously. I knew I had a fractured fibula, something I could clearly see in the x-ray that lay next to me on my stretcher, but I wasn’t aware I had sustained a tibial plateau fracture— a serious injury that meant the main weight supporting bone in my right leg was fractured near the knee joint.

I wasn’t going to call anyone, refusing the repeated offers of medical personnel handing me their mobiles, but eventually I accepted. Using one of the nurse’s phones, I called my family back in the states. What I wasn’t aware of at the time in Honduras, lying in that hallway, was that call set off a chain reaction in the states. Cathy, a family friend, contacted her Honduran friend Antonio, whose family lived in the city I had wrecked outside of. While I lay in the hallway shaking in the dim light, his family had been searching every hospital in the area for me, asking if a foreign girl had been admitted from a motorcycle accident.

I was so cold, covered in gravel and dirt, my back raw with road rash. The dimly lit hallway ended in a door at one end, a corner at the other. I lay on a thin plastic mattress, an IV bag laying on top of me, disconnected. As I shook, naked underneath the thin gown, the young nurse I had seen in the examination room walked past. He took an interest in me, taking my vitals and gave me his mobile to call my family in the states, where I was able to tell them what hospital I was at.

“You might get into surgery soon, maybe tonight, maybe tomorrow, maybe the day after,” he said.

***

San Pedro Sula, Public Hospital // Friday, 11 PM

“Bend over, and we’ll inject the anaesthetic into the base of your spine. Count backwards…” I woke up to white, bright lights, a curtain separating my upper body from the rest of the room. “Como esta mi pierna?” I shifted groggily, then darkness.

My body was surrounded by frigid air. I could hear the sound of the metal bed rolling across the floor. I was moving. The florescent lights overhead shone through my closed eyelids, a haze of pink and cold and numb. I was in a large room filled with metal beds, naked save a thin green gown draped over my body. I looked to my left, a young man was lying there in a bed looking just as groggy as I did. I smiled at him.

A man walked over to my bed. “Hi, I’m Rafael, Antonio’s nephew. I’ll be back to check on you tomorrow morning and bring you something to eat.” He gave me a pair of athletic pants, and helped me pull them on over the new plaster cast on my right leg. I was so groggy from the surgery, I barely registered what was happening. I found out later, the only reason I had gotten into surgery that night was because Antonio had called in favors with his contacts, and Rafael knew the orthopedic surgeon.

A man came and wheeled me into an elevator, then down a hallway into a dark room. “Can you bring me some water please?” I croaked. At that point I didn’t know whether I was speaking Spanish or English, I had never been so thirsty in my entire life. I hadn’t had something to drink for 18 hours, since I rode out of the jungle that morning. I waited for someone to return. No one did.

The room was dark, several people at the other end illuminated by the shapes their bodies made against the glass. I was deposited on one of the beds in the middle of the room— a thin, empty plastic mattress. I lay against the plastic, bits of dirt and gravel sticking to my back from the accident. My hair stuck to the back of my neck, my leg sticking straight out on the bed in a half plaster cast. I was so thirsty I couldn’t think of anything else. I started to get desperate— there must be a water supply somewhere, I thought, but I couldn’t walk to get to it.

The room was flooded with light as a woman from the far end of the room left, leaving the door open a crack behind her. I struggled to sit up— my entire lower back and upper butt was raw and damp from being scraped across the highway, and my leg in a cast. I made it up to my hands, pulling my body slowly back with my arms.

A few moments later, the door opened again. “Disculpe,” I asked in Spanish, “Could you please bring me some water?” I was so desperate for a drink. “Please.”

She went over to her bed, brought back a bottle of water and a large cup, and poured me a glassful of water. I gulped it down, I didn’t even stop to breathe. She poured me another, and I drank that one just as quickly. “Thank you, thank you,” I told her gratefully in the dark, and slid back down the plastic mattress into the darkness once more.

***

I woke in the grey light, the large room visible by the light pouring through the glass window at the far end, green trees and a pale sky in the distance. There were four beds in the room, one to my left, and two more beds to my right. Each bed was adorned in what looked like personal belongings from home, patterned sheets and pillowcases, blankets and oscillating fans. One person sat next to each bedside, all women— they had slept there overnight in small plastic chairs, heads leaning against the foot of each mattress.

Three women gathered around the foot of my bed, asking me what had happened and why was I there at the public hospital. One of the women left the room, and came back with a patterned sheet, and before I knew what was happening, they had half lifted me up, pulled the sheet over the mattress, put a pillow behind my head, brought me a juicebox and a bottle of water, and angled one of their fans toward me.

I asked them where the doctors were, I hadn’t seen anyone since I was wheeled in late the night before.

“You won’t see anyone before Monday,” one woman told me in Spanish, “The medics don’t work on the weekends.”

***

San Pedro Sula, Public Hospital // Saturday, 6 AM

Rafael, Antonio’s nephew, arrived early that morning. I found out later he had worked an entire shift before ending work and coming to visit me, where he stayed the rest of the day. He pulled up a chair next to my bed, noting how the women in the room were taking care of me. He recommended I move to a private hospital where I’d receive regular, quality antibiotics. One of his friends worked at a private military hospital in San Pedro Sula, and later that day he pulled strings to move me there, even though it was full. He went to the hospital to arrange everything, confirmed the daily price of a bed and quality antibiotics (“Give her the best stuff you have,” he told them). While he was gone, his grandmother Rafaela sat with me at the hospital, trying to get me to eat something.

Shortly after Rafael returned, a man and a woman arrived with a stretcher and clipboards to take me to the military hospital. We were still waiting for the nurses at the public hospital to sign the release paperwork. I hadn’t had any antibiotics since surgery the night before, which was critical, because of my open fracture and how contaminated the wound was— during surgery the night before, the orthopedic surgeon spent hours cleaning gravel out of my leg.

All of a sudden, I heard shouting in the hallway, and Rafael came storming into the room. “We’re going,” he said, “without the release paperwork.”

I was transferred onto another stretcher, another ambulance, that bounced over speedbumps and potholes. We arrived at the private military hospital, a clean, sunny yellow place, where I was able to see the sky as they wheeled me under the awning and whisked me behind a curtain to put me on an IV with the strongest pain medication I’ve ever experienced. I tried to ask them to stop, but found I could no longer form coherent words.

I ate dinner with my bare hands— my movements becoming increasingly wild as I tried to find and hold the lettuce with my right fingers, my dominant left hand held captive by the IV pumping gasoline quality antibiotics into my veins. Eventually I gave up as my shirt was littered with lettuce and bits of dressing. I remember trying to joke with the nurse about it (which realistically at that point, was probably nonsensical babble) who gave me a strange look, then left.

They took an ultrasound of all my major organs as I tried to joke with the doctor, but again, I could barely form a sentence. Afterwards, I spend a fun half hour in the x-ray room with two Honduran men, where we darkly joked about motorcycle accidents and talked about riding in Honduras and the United States, and traded English and Spanish slang.

“Why aren’t you crying?” one of the men asked, as we took the fourth x-ray, while I twisted myself and my broken leg unnaturally on the table. “If you were a man you’d be crying,” he said.

One of the men told me how his young son had also been in an accident earlier that day. He had climbed onto the family’s scooter and taken it for a brief ride before falling off and hitting his head. His family was at the hospital with his son in another city at that same moment. “I’m so sorry,” I said, “I wish you could go to him.”

“Someone carry my son, now I carry you,” he said.